A single woman hitting her 40s, looking for romance, describes her brushes with the 'bad boys of Delhi'

How about dinner tomorrow, he countered.

Among the pool of single men in the city were a handful of bachelors in their forties and fifties, who fancied themselves as desi James Bonds, based on a grandiose, often delusional self-image. They moved in the fast lane, apparently maintaining a series of casual sexual liaisons. I was told that women gravitated like bees around these rich guys despite their obvious shortcomings: obesity, pomposity, lack of charm and rakish behaviour. Witnessing the modus operandi of one such character was an entertaining experience.

I was introduced to Samir at a friend’s fiftieth birthday party. He was short and podgy, about my age, and spoke English with a Hindi enunciation. The ladies flocked around him though. Clearly he had some X factor, which was hard to put a finger on.

“Samir is a topnotch lawyer,” whispered Arti, the hostess. “Handling the defence in the Pinky Lal case.”

The Pinky Lal case was a high profile tabloid case, in which a rich businessman was suspected of murdering a fashion model, Pinky. The suspicion was that he had pushed her off the balcony of a five-star hotel, though his defence team insisted that the victim had been under the influence of drugs, leading her to leap to her own death.

The knowledge that Samir was defending a rich murderer made me uncomfortable. I shrugged off the feeling, and picked up a chicken mini-quiche, savouring its flaky pastry. Getting a quiche pastry right was a real art, and I made a mental note to ask Arti who the caterer was.

Bollywood music was on full blast, and the floor was crowded with dancers.

“Come on Ritzy, don’t be shy,” shouted someone, pulling my arm and dragging me into the shaking, sweaty mob. I swayed a bit, trying to get into the rhythm. I’d grown up dancing to Boney M and Earth, Wind & Fire, and “Pappu Can’t Dance” kind of music didn’t fire up my mojo.

But others seemed to have no problem. Samir lurched towards me, holding the hand of a woman in her twenties, snug in black leather pants.

“Hi Ritu, we met earlier, remember?” he said, rotating his shoulders with abandon. I stepped back and gave him a lukewarm smile.

Now, every woman knows about Indian men and alcohol. A few drinks down, and they start behaving as if the world is their playpen. The drunk Indian male can be spotted from a mile off at parties, clubs and planes. He totters about, slurring his words, making ludicrous statements and leering at every woman who crosses his path. If there’s a dance floor around, he’s sure to be weaving around, hands in the air, trying to brush his manly chest and every other part of himself against the bodies of females in the vicinity.

Samir looked like he was about to reach that stage. He gyrated aggressively beside me, prompting me to move off the floor, to avoid crashing into him.

“We are going to a nightclub after this, why don’t you join us,” he shouted, above the din. “It’ll be good fun.”

I said no quickly, wondering what his game was. Why did a guy who already had a woman hanging onto his arm want a kebab mein haddi? Or did he want a ménage a trios? I didn’t stay long enough to find out.

I ran into Samir again at a book launch, and this time we struck up a conversation about his pro bono work for an NGO working in the field of child rights.

“I have filed five cases for them this year,” he said proudly.

“That’s great,” I said, chiding myself for having misjudged him: Maybe he’s not so bad after all.

I told him about my own work at the Women’s and Children’s Centre.

“I knew you and I had a lot in common when I saw you, Ritu,” he said, a glint in his eye.

“Let’s have a drink soon.” He squeezed my hand before moving away to strike up a conversation elsewhere.

Six weeks later, he sent me a text: U want to come to the Siddhartha Mukherjee book launch tonight?

I contemplated his invitation. I was curious about Mukherjee, a US-based physician and oncologist who had authored the Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. For the past few years, I’d been a writer for the Elle magazine breast cancer campaign, and had a keen interest in learning more about the disease. But at that moment, I was too tired to relish the thought of being crushed in a room with others keen to catch a glimpse of the celebrity writer.

Long day at work, I texted Samir. Maybe another time.

How about dinner tomorrow, he countered.

Now, Samir really wasn’t my type: he was too plump and self-important. But I decided to be to give him a chance. “Chuck the checklist,” I recalled some expert say on a dating show. I said yes to his invitation and justified my decision by telling myself that I was just following dating advice. After all, so many friends had told me to be more “open” to different kinds of men, though I never quite understood what this meant. Open to what? A Sai Baba follower? A taxi driver? A guy ten years younger than me?

Despite my skepticism, I indulged in the fantasy of being swept away by someone completely unlikely. Why not Samir? Hypothetically, he was a good candidate for romance. He was single, my age, professionally successful. So what if he seemed a bit sleazy… or that I had to fight an impulse to correct his pronunciation every time he opened his mouth? What was the harm in checking him out?

We set up to meet the next evening, and Samir arrived to collect me in a chauffeur-driven black BMW. He stepped out of the car to greet me, and opened the door with a flourish. I slid happily into the smooth back seat beside him and murmured, “Nice.”

He looked pleased. “Need to maintain my image… being a high-powered lawyer isn’t easy,” he said, making a face to indicate the effort involved. “I have to walk the talk, you know.”

I raised my eyebrows and tried to stifle a laugh. We coasted along to a five-star hotel, and spent a couple of hours downing fish fingers and margaritas. Samir boasted about all the high-profile clients his firm handled: the Pinky Lal case, and yet another murder trial in which his firm had represented the accused (despite his obvious guilt) and even got him acquitted. I asked him how he felt about letting a murderer loose on society.

“Arre, I would have defended OJ Simpson if he made it worth my while, so why not this guy!” he responded with a laugh.

I was appalled, but decided to give him the benefit of doubt. Maybe he’s just joking?

Samir went on at length about the cases of fraud, embezzlement and insider trading, which were in the news. We discussed the good-looking girlfriend of a politician he socialised with. The bill arrived. He opened his wallet, and picked out a credit card slowly, making it a point to linger so I could get a look at the dozen cards on display.

When we got back into the car, he squeezed my arm and gave me a suggestive look. “I’ve arranged dinner at home,” he said. “Hope that’s okay?”

“That’s fine,” I said. May as well get a close up and see what lies in your bathroom cupboards. He pressed his thigh against mine, in what seemed to be an appreciative gesture. “Wait till you see what I’ve got lined up for you.”

My willingness to break the rules of dating and jump ahead to meeting a man in his own house, was more a reflection of my impatience, than my sexual liberation. My logic was: why bother with the fancy dinners if the clues to his personality lie in his living spaces? I was curious about the books people read, the spices in their kitchen and the pictures on their walls.

Samir’s flat was located in Jorbagh, one of the most expensive real estate zones of the city. The moment we stepped through the front door, he whipped me off on a tour, beginning with the guest bedroom. “See—this is an Anjolie Ela Menon,’ he said, indicating the giant painting of a Madonna-like figure, wearing a crown of thorns.

I murmured appreciatively.

“That’s an Arpana Caur, of course,” he boasted, indicating the massive canvas that had a woman holding a pair of scissors as its focus.

“Did you know that Caur uses scissors as a metaphor for time?” he said, “Based on the Greek belief that scissors can cut a man’s fate.”

I made some appreciative sounds, though I wasn’t convinced by his speech.

Nothing in his demeanour projected the artistic sensibility he was trying so hard to impress me with. We moved from one room to another, with Samir pointing out the noteworthy objects in each.

“It’s a 72-inch screen,” he said, indicating the TV facing his double bed.

“Carried it with me, all the way from Hong Kong so I could watch Pretty Woman properly.”

I expelled my breath impatiently: what to say about men and their obsession with giant plasma TVs? Or their fantasies of turning whores into wives? Maybe the latter was more of a possibility, than that of an ugly frog turning into a prince-like husband after all.

My gaze fell to the open suitcase on his bed.

“I’m travelling to Venice tomorrow for a friend’s wedding,” he explained, adjusting the suit that lay neatly folded on top.

“All my suits and formal shirts are stitched in Italy, and dry-cleaned only at the Hyatt hotel, you know,” he said, plunging into a long and tedious explanation of where he bought the fabric, how he ensured that he had one case a year in Milan so that he could get his tailoring attended to.

“And here, my assistant maintains my clothes perfectly — they’re washed, starched and ironed immediately after use, to avoid stains and smells from accumulating.”

I swallowed a caustic comment, wondering how he would react if I told him that I never dry-cleaned anything, and that I bought most of my clothes at Sarojini Nagar market. Samir’s conceit was worth marvelling at, though.

I was amused that he imagined that I — or any other woman who wasn’t his wife — would be interested in the mundane details of his grooming routine. Perhaps I should have been impressed at his domestic self-reliance? Obviously, he didn’t need a wife to help him maintain his wardrobe. In that sense, he was different from other bachelors I’d met. Maybe his redeeming quality was that he would more likely marry a woman for love, or the value she added to his show-and-tell routine, than to clean up his mess!

***

The showpiece of Samir’s study was his iSymphonic Massage chair, a chair that synchronised massage with music.

“Did you know that it was voted ‘invention of the year’ by Time magazine,” he said eagerly.

“Come and try it.” What the hell, I thought, plonking myself on the plush seat. Samir adjusted the settings. “I’ve programmed a fifteen-minute neck massage for you,” he said.

The chair started moving to the tempo of Four Seasons by Vivaldi. I sat back and mused about Samir’s constant references to money. Clearly, he was deprived at some level, and hadn’t recovered from this experience. Most of the wealthy guys I knew fell into two categories.

The first were born rich and grew up in an atmosphere of privilege, sent off to Modern School, Doon or Sanawar, followed by college in the UK or US — Oxford, Harvard, Stanford or Yale if they were smart enough. Sure, they threw their weight around, but their comfort around money was apparent. They were even casual about it, since they had never known any kind of material deprivation. From his hints, I gathered that Samir belonged to the second category, those who were born poor or middleclass, and acquired wealth in their adulthood. They were smart and lucky (both generally) to become rich adults.

But they never stopped obsessing about their wealth or pushing their good fortune in other people’s faces.

Fifteen minutes of the chair massage relieved the tension in my neck. Samir was ready with his next move. He led me to what he referred to as his “party fridge”. This was packed with wine and chocolates. From the details that peppered his conversation, I gathered that this was part of his courtship ritual. Every woman invited to his apartment was granted access to this fridge.

“Let’s have some chardonnay,” he said, pulling out a bottle, “I just picked it up in Paris.”

I ignored him, transfixed by the chocolates: there were at least ten boxes of Godiva chocolate raspberry truffles, truly the smoothest, melt-in-your mouth chocolates I’d ever eaten in my life. Behind this stash were some giant bars of Cadbury’s milk chocolate.

“How come you have Cadbury’s,” I exclaimed, “I thought they were out of fashion.”

My comment pleased Samir. “Not at all…they are one of my favourite brands…I just love Cadbury’s milk chocolate,” he said, pulling out a bar and handing it to me. “Here’s one for you.”

I held the chocolate lovingly, wondering how he would react if I tore the packet open and began eating it. But Samir was too wrapped up in himself to notice my greedy reaction.

“The UK Cadbury’s is the best, you know, Ritu,” he said, holding up the chardonnay for my approval.

“I prefer Sula White actually,” I asserted, just to be contrary.

He grimaced and slid the bottle back in the fridge. “Sab ka apna apna — there’s no accounting for personal taste,” he said, carrying the Sula and two wine glasses into the drawing room.

We sat down on the white sofa, and after some banter about our work, the conversation moved to relationships. I asked him about the woman he was with at the party. He laughed dismissively. “Oh her… she’s the daughter of a high court judge. I was just entertaining her since she was in town that day.”

I then asked him whether there was any truth in the rumour that he was involved with a mutual friend of ours — I didn’t want to get caught in the middle of anything.

“How could you even imagine me with her, Ritu?” he said, in a pained voice.

“I only go out with good-looking women.” I gulped my wine, taken aback by his chauvinism, and this negative judgement of our friend.

So, her looks didn’t meet his standards. What a creep. Had he actually looked at himself in the mirror properly?

“Actually I have a gorgeous girlfriend in Venice,” he said quickly, seeing that I was put out.

A bearer brought in a plate of chicken tikkas, and I was distracted. I took a bite of the succulent morsel on my plate and savoured it, in an attempt to regain my composure.

“Oh really… so the long-distance relationship thing works for you then?” I ventured.

“Oh come on, Ritu, there are trains and planes! We get together whenever we can,” he began.

“The rest of the time we are free to pursue other options… it’s an open relationship… there are so many beautiful women out there… ”

My distaste built up.

His “I’m the greatest guy in the universe” stance was like a wall he’d built to support himself. And adulation was his biggest craving, so when it came to women, Samir was on the lookout for ladies to fan his narcissism.

In return, he was ready to open his wallet. Even though he was ageing and not particularly attractive, his wealth ensured him a steady supply of women agreeable to this arrangement.

“I’m glad you’ve got it all sorted out, Samir,” I said, in an even tone.

He refilled my wine glass and moved close to me. His hand reached out for my knee.

“You are a sexy woman, Ritu, and I’d love to spend more time with you,” he murmured.

“And you can trust me — my lips will be sealed.”

I took his hand off my knee, and excused myself to go to the bathroom.

I stared at my reflection in the mirror: dishevelled, flushed, from the wine and irritation, and definitely tired.

Why had I put myself through the whole wine-and-dine routine with a guy like him, who bribed me with a session in his massage chair and a bar of imported chocolate, to induce me into his bed?

Of course, it was my fault.

I’d agreed to have dinner at his house and he’d imagined that my apparently progressive attitude meant I was up for casual sex.

How was he to know that his bed-hopping ethos was as off-putting to me as his bragging? Or that his offer to maintain secrecy about our sex life — if we ever had one — was probably the worst move he could have ever made. Men like him made sex dirty, I mused, tearing open the bar of Cadbury’s and popping a large chunk into my mouth. By the time I walked out of the bathroom, I was clear about one thing: if a guy looks sleazy, he is sleazy.

I’d heard some stories about the bad boys of Delhi, who charmed the panties off women and disappeared soon thereafter. Their role models were Hollywood heroes like Jude Law and Colin Farrell, whose rakish charm was reputed to drive females mad. Though women instinctively knew that they wouldn’t get a lasting relationship out of them, very few had the willpower to resist them. Hymens and hearts were broken as these charming and commitment-phobic men moved from one woman to the next.

None of the men I met even remotely resembled Jude Law, so I didn’t believe the rumours. “Maybe people refer to sleazy characters as bad boys here,” I remarked, to my friend Poonam, while we sipped happy hour cocktails at TGIF.

“Maybe,” she said, “but we do tend to fall for the wicked guys… maybe because we know we can’t ever have them, you know.”

We were on our fourth glass of Long Island iced tea, and Poonam was swirling on her bar stool a bit too vigorously.

“Let’s accept that we are total suckers for men who take us for a spin,” she giggled.

I laughed disbelievingly. The thought of falling for a commitment-phobic party boy was ludicrous. Why waste time playing dead-end seduction games with anyone? I couldn’t imagine being a plaything for any man.

My confidence in my capacity to automatically reject anyone with bad boy characteristics didn’t prepare me for my first encounter with one.

I met Mukesh through an ex-colleague, Ravi, at a wedding reception. Ravi introduced him as a “chum from school”, and started telling him about me, recounting the time we worked together on an NGO project in the red-light district of Mumbai. Our job was to persuade sex workers to enroll their children in school. Mukesh’s eyes lit up with interest at Ravi’s description of the brothels we visited.

“What was that like?” he asked me curiously.

“A bit dismal,” I said, feeling a little ashamed about this admission. “The place was a giant slum and the rooms were like hovels… and the women conducted their business while the kids played outside.”

****

Mukesh moved closer to me and gave me one of those appraising looks, which started from my hair and eyes, paused at my breasts, before flicking downwards and ending at my toes. I shifted my weight from one foot to the other. The gaze of the male hunter seemed outdated, so I decided to get even by subjecting him to the same assessment.

Mukesh had a dusky complexion, high cheekbones, and gelled hair. He wore a slick navy blue suit, with a mauve tie, which reminded me of Robert de Niro in Casino.

He was good-looking in an Italian mobster kind of way too. Both of us reached out for a glass of red wine when the waiter made his rounds with the drinks tray.

“Aha,” said Mukesh, giving me another appraising look, “so we do have something in common after all!”

Ravi raised his glass of whisky, and we followed suit.

“Cheers!” “Is wine a dancer’s drink or what?” Ravi asked Mukesh mock-seriously.

“Probably,” replied Mukesh, “since it’s the only alcoholic beverage you can drink without worrying about losing your balance.”

“Really?” I retorted. “So how many glasses can you drink without feeling tizzy?”

“Two… three maybe,” he responded.

“What about you?”

“Wine isn’t really my drink,” I said.

“I’d rather have a chilled beer.”

Mukesh made a face and put down his empty glass on a nearby table.

“So why didn’t you have beer today?’ He gestured to the waiter for another round.

“I’ve got some work to finish when I get home,” I said, sipping my drink slowly, “and beer makes me sleepy.”

Ravi nodded in agreement.

“Remember the beer promotion event we went to?” he said.

We launched into another nostalgic chat about past lives.

“So Ritu, what do you do over the weekend?” quizzed Mukesh, cutting into our exchange.

“A bit of this and that,” I replied, wondering which of my interests I should talk about. Reading? Baking? Watching movies? Working out? It was easier to throw the question back at him.

“What do you do on holidays, Mukesh?”

“I spend all my free time in my dance studio,” he said.

“Latin dance is my thing. Can you do salsa or zumba?” Ravi’s dig at him about wine being a dancer’s drink now began to make sense, but I wondered whether he was serious: did I look like a zumba or salsa dancer?

“Oh no,” I replied quickly.

“I love music but I really can’t do any dance except disco-style shaky wiggly stuff. I’ve absolutely no sense of co-ordination.”

Mukesh raised his eyebrows in amusement at my statement.

“Shaky wiggly stuff…that sounds exciting. But I can teach you salsa if you want,” he murmured.

I kept silent, not sure how to respond: why would I want to learn dance from Mukesh, or anyone for that matter?

“Do get in touch if you’re interested,” he said, unperturbed by my discomfort. He handed me a blue business card from his wallet.

Mukesh Rastogi, it read. Below his name was a long list of qualifications. The MBA from Wharton caught my eye.

“I work in the family business of stock market advisory, with my dad,” he explained, mentioning an address in Connaught Place.

My interest was piqued. How often did one meet a guy with an MBA who was an expert salsa dancer too?

Most guys I knew were relatively unidirectional.

They were boxed into their careers and identities.

Mukesh appeared to have chucked the standard formula and devised his own, more innovative one. I put his card in my handbag and gave him one of my own.

“I’ll give you a call,” he said, his gaze skittering across the room.

A moment later, he was gone. I looked at Ravi questioningly. “Who is this guy?” Ravi gave me a quizzical smile.

“He’s good company and a great dancer — that much I know, but don’t get too cozy with him. I’ve been told he’s a big ditcher when it comes to women.”

***

The thought of Mukesh crossed my mind a few times after our encounter, and I wasn’t surprised when he called.

“So pretty lady, how’s it going?” he said breezily.

I told him about an article I was planning, on dance therapy, and asked if he would introduce me to his clients who could talk about the physical and emotional benefits of dance. He responded enthusiastically.

“That’s fantastic. I’m going to put you in touch with some people in my class.” I thanked him, feeling strangely gratified about having found some way of connecting with him. I needn’t have worried though, since he had worked out his own route.

“Listen, I’m calling to invite you to my birthday party,” he continued.

I smiled at the excitement in his voice; it was rare to meet a guy in his forties who made a big deal of his birthday.

“I’d love to come,” I replied. “Please text me the address.”

The party venue was a farmhouse on the outskirts of the city. There were lots of cars with CD plates.

Little fairy lights twinkled on the trees, and from the gate, I could see the large gathering of guests at the far corner of the sprawling garden.

Strains of Latin music filled the air, and I was instantly lifted by the atmosphere of festivity. I spotted some well-known artists, designers and business magnates, lots of glamorous women and some Western men.

Waiters wandered around serving vol-auvents and stuffed mushrooms, and Mukesh stood in the midst of a group of women, dressed in a tight black suit.

“Hey, glad you could make it,” he said, giving me a European-style peck on both cheeks and taking my gift of red wine from my hands.

“Let me introduce you to my friends.”

An hour later, I moved with the crowd to a dance floor set in a courtyard, below the trees.

Couples shimmied away to the rhythm of a salsa song, “Oye Como Va”, being belted out by Celia Cruz. I mused about how much better I liked Santana’s version, and gazed enviously at the floor full of dancing people.

My attempts to learn formal dance of any kind had never met with much success. I never seemed to get the steps right and partnering with a man on the dance floor didn’t come easy either. Every time I did one of those couple numbers, I’d tug at my partner and frustrate him. I just couldn’t let anyone take the lead. I thought about my ineptitude as I watched Mukesh dancing with a slim olive-skinned woman in a short black skirt and heels that looked like killers.

They were a joy to watch together: Mukesh moved his torso and shoulders smoothly in sync with the drumbeat, and led his partner with the same ease. In a flash, I could see what made him so attractive to women. His agility and easy reading of his partner’s rhythm were sure bait. I came away from the party with mixed feelings.

My attraction to Mukesh had intensified, but I also felt insecure. What was the point of even considering starting up something with him?

He was so different from me: so smooth, flamboyant and easy in his body. How could I — a middle-aged, not-so-thin woman with zero grace on the dance floor — possibly match up to the young, agile women he danced with every day? What were the chances of my assimilating into his world of dance and music? And how would he fit into my world? I wondered whether he’d be able to contribute to a conversation about health systems, or medicine. With a sigh, I realised that the chances of coupling successfully with a man like him were almost nil.

Still, I couldn’t curb my elation when he called to invite me to accompany him to a dinner party.

“It’s at a good friend’s place…he’s a great host.”

I accepted his invitation, not pausing for an instant to worry about the risks of accompanying a man I barely knew, to a stranger’s house. Mukesh began describing how he and Bobby used to be best pals at school.

“Now his wife and her friends come to my dance studio, can you imagine!” he said.

I laughed, despite my uncertain feelings. Every woman in his circle was either a dancer, or on her way to becoming one. The only way to belong was to follow suit.

“Any dress code?” I asked, tentatively.

“Wear something revealing,” he responded, with a guffaw.

I was taken aback. Was he serious? I recalled the beautiful women at his party, with their bare-backed dresses and plunging necklines. Nothing in my wardrobe came even close to glamorous, let alone revealing. He sensed my hesitation, and was quick to cover up.

“Just kidding. You look great in everything.”

I took hours trying to decide what to wear, trying out unworn blouses and skirts from the piles at the back of my cupboard and peering at my reflection in a mirror. I would never have the lithe body of the female dancers he was used to. I convinced myself to wear a pink blouse that clung to me anyway, and a vivid five-panelled skirt designed by my friend Komal. From under the bed, I pulled out a pair of purple spangled sandals that had been lying in a shoebox since I bought them a year earlier. I tottered around in them, recalling my excitement when I first saw them, in the shop of a Chinese shoemaker.

“When will you ever wear fourinch heels?” chided my sister, in an attempt to dissuade me from buying them.

I mused about sending her a picture.

Mukesh made lots of admiring noises when he picked me up.

“You’re looking really hot,” he said, giving me his signature top-to-toe look, as I slid into the front seat of his car.

“Pink suits you.”

I flushed at his obvious appreciation, and fought back my amusement: wasn’t the word “hot” best applied to someone half my age?

But then, Mukesh was a 45-year-old who acted as if he was twenty-five. He even lived the life of a much younger man. We drove along in Saturday night traffic. The dinner party was in Gurgaon, so there was a long way to go.

To my surprise, he turned on some opera, and began humming along with Pavarotti.

The leather interiors of the car throbbed with the emotion, and my heart leapt. “I’m learning to sing opera myself, at the Italian embassy, twice a week,” he divulged.

“That’s wonderful,” I murmured, marvelling at whatever force on the planet had placed me in a car with a salsa dancer and self-proclaimed opera singer, after months of hanging around with a slew of dull men.

“You know dance and music has changed my whole life,” he said reflectively.

“I was a complete non-entity at one time.”

“That’s hard to imagine, Mukesh,” I said, struggling to summon an image of him as a nondescript everyday man, who went about business as usual. I also bit back my urge to tell him how stunning he was on the dance floor — all the dating guides I’d read stressed holding back feelings, and prolonging a man’s uncertainty.

“I never got a second look from anyone when I was in college,” he continued.

“And none of the girls wanted to go out with me.”

He said he’d started learning dance as part of a personality enhancing exercise.

“I knew I wasn’t smart enough to become a rich man and lure the girls with my money,” he said.

“So I bought some dance tapes and began practicing in my bedroom… who knew that I’d be running a dance studio twenty years later!”

“You’re lucky to have found your calling,” I said.

My thoughts strayed to some people I knew, who’d been stuck in dead-end jobs and marriages all their lives, and never had the courage to follow their passion. Timing really mattered, and Mukesh’s success in capitalising upon his passion for dancing had much to do with the fact that he’d taken this up early, when he was young and energetic enough to chase whatever he wanted.

“Yes, but what to do about the wine-drinking?” he said playfully.

“You tell me, you’re the health expert.”

Apparently Mukesh had just recovered from a hepatic infection.

“I spent a month in hospital, and the doc said I needed to cut back on the booze, long-term.”

The image of his vulnerable liver loomed in my head, and I could feel my protective instinct coming to the fore. I searched my brain for whatever I could summon up about liver health.

“That’s bad — but there’s no choice — recovering liver health is a long process. You’ll need to avoid booze, fried foods, too much exertion,” I cautioned.

“You must eat a bowl of dahi every day.” He nodded, looking bored and simultaneously worried.

‘I’m trying. But you know wine and dance go together… sometimes I lose track of how much goes down,” he sighed.

I started to speak again, and stopped, reminding myself of one particular session with AD years earlier, in which she’d said: Stop trying to mother, advise and fix every man you meet. Indeed, playing Mother Teresa had failed me in the department of love: how easily stories of let-down and despair triggered my self-sacrificial tendencies. I decided I would be ultra careful about keeping this particular tendency of mine under control, this time round.

I gave Mukesh an affectionate pat on his knee instead, and he closed his hand over mine, giving it a squeeze. I left it there for an instant, letting the surge of warmth from his touch course though my fingers. But Mukesh broke the spell.

“I need to pick up some flowers,” he said, veering off the highway, and stopping near a flower vendor. He turned to me beseechingly.

“Could you help me choose? I don’t know anything about flowers.”

The party was in full swing when we walked in. The host, Bobby, and his wife Safina greeted Mukesh effusively. They tried to look impressed when Mukesh introduced me. “Ritu is a big-time journalist who writes for all kinds of papers and magazines.”

Safina’s attention had already wandered to another couple who had just entered the room.

“Excuse me,” she said, traipsing off in her chiffon saree. I moved my weight from one foot to the other, trying to distract myself from my discomfort as I looked around and realised I had chosen the wrong clothes for the occasion. My tight blouse and billowing skirt were totally inappropriate, since all the other women were clad in sarees or salwaar kameezes.

Why hadn’t Mukesh warned me? I glared at him balefully.

“Let me get you a beer,” he said, gently steering me towards the bar. He greeted several people on the way, shaking hands with the men and exchanging plenty of air-kisses with the women. “She takes my classes,” he’d say, indicating one woman or another. I nodded each time, astonished that salsa was such a popular form of dance in Delhi.

The hostess suddenly appeared before me, and took me to a group of women.

“This is Ritu — Mukesh’s friend,” she said, emphasising the last word and giving me a knowing look and wink.

I started opening my mouth to protest, but stopped. What was the point? I had already been branded. Yet again, my tendency to overlook the implications of my actions in the arena of relationships, or worry about how they could be misread, was my undoing.

Self-recrimination flooded through me, until Mukesh reappeared to distract me. His hand skimmed the small of my back, before he started greeting the others in the circle.

I envied the ease with which he stepped in and out of the female orbit, which contrasted so sharply with my own awkwardness. My wariness with married women in social situations tinged my interactions.

Finding common ground hadn’t been easy since I’d become a singleton. Their conversations revolved around husbands, children, in-laws, maids, vacations and shopping trips. I had nothing to contribute; my concerns were different, as were my victories: discovering a great plumber, paying rent on time, and publishing an article in a paper with a wide circulation.

I wondered what they’d make of my mission to find Mr Right. “So what do you do?” ventured someone bravely.

“I’m a health writer,” I replied, trying to sum up my entire existence in one sentence.

Fortunately, this elicited lots of chatter about diets and weight problems, and I relaxed as the evening progressed. Mukesh hovered around, never letting me feel abandoned.

He seemed to have his finger on my pulse, sensing when I was restless or hungry, or simply needed rescuing from a conversation. He watched my glass, refilling it whenever it fell empty and kept bringing around the bowls of nuts and chips. The rest of the evening was spent in a haze of pheromones.

Everything he said or did simply worked to build up the fantasy I had created about him. He picked up on my vibe, bestowing me with all the attention and alcohol I could possibly want. Two hours later, I was wilting.

“I’m really tired,” I moaned, grabbing his arm.

“That’s because you haven’t had the right drink,” he purred, “I’m going to make you a special one.”

Despite my protests, he walked away to the bar and came back bearing a glass filled with a red drink. I reeled after my first sip.

“It’s heady, just like you,” he said, stroking my arm.

“I can’t wait for it to hit you.”

Before I could respond, a group of women waved to him, and he responded by summoning them over. There was plenty of laughter, and a round of introductions. While Mukesh basked in their attention, I abandoned my drink on a nearby tray. Ten minutes later, I pulled at his arm.

“Let’s go, please, it’s really late.” This time, Mukesh knew by my tone that I meant business.

We got into the car in silence. Mukesh opened the glove compartment to retrieve the glasses he used for driving at night.

“Where the hell are they,” he muttered, rummaging around noisily.

Something fell on my feet. We bent down to pick up the packet simultaneously. I froze when I saw the box of Masti condoms resting against my silvery purple sandals.

Mukesh picked it up nonchalantly and put it back in the compartment.

“Now you know I practice safe sex, right?”

When Mukesh dropped me home an hour later, I was tempted to invite him in. But I decided against it, and wished him goodnight with a peck on his cheek.

Despite my attraction to him, I wasn’t ready for a physical relationship. Even if I took the plunge, I wasn’t sure about my readiness to handle the repercussions.

Would I fall into the familiar trap, the blame game I’d witnessed so many progressive and liberated women playing? He lured me into bed… He used me… I recalled conversations with outwardly bold and brazen women who pretended to be sexually liberated, but couldn’t resist accusing men of “taking advantage” of them when copulation didn’t lead to the commitment they sought.

There was M, an ex-colleague who had all the men lusting for her, with her plunging necklines and skimpy skirts. She used the F word in every sentence and was open about her affairs with various men, including her bosses.

Known for getting entangled with “unavailable men”, M believed it was perfectly acceptable to have sex with guys on the first date. She hounded them thereafter, calling them up a dozen times a day to suggest more dates, and was heartbroken when the men didn’t return her calls.

Once, she and I got into a heated discussion over whether society had the right to blame men for the suicide of women they’d jilted.

The sensational story of a failed love affair that had led a supermodel to jump to death had just broken.

The 23-year-old had left a note blaming her boyfriend for failing to deliver on his promise of marriage. “What a bastard… any man who promises a woman he will marry her and doesn’t, after sleeping with her, should be jailed for life,” M ranted, taking a deep suck of her cigarette.

I sipped the watery coffee from the office machine and wondered if she was saying this for dramatic effect. But M was dead serious. Her forward sexual behaviour conflicted with the meaning she attributed to sex, and I suddenly realised that her swaggering bravado was just a cover up for her vulnerability.

“How dare these guys assume they can f…k whoever they want and get away with it.” Linking sex to love is one matter, but tying it up with marriage was ludicrous.

I tried to reason with her. “What about sexual freedom? How can we be at par with men we sleep with, unless we exercise the same choice as them… attribute as little or as much meaning to the sexual act as they do?”

M gave me a dirty look, threw her cigarette to the floor, and crushed it with her heel. From this conversation, I realised that easy sex isn’t as easy as it looks, even for bold women who fight against gender stereotypes and take pride in “living like men”. Claiming sexual power was nearly impossible for my friend Avantika, who had plenty of other masculine traits she enjoyed boasting about. She had walked out of a bad marriage without a second thought, and successfully negotiated big business deals. But she just couldn’t handle a sexual relationship that came without strings.

Ironically, Avantika was an Oshoite and used her guru’s philosophies of love to justify her clandestine relationships with married or otherwise unavailable men. Marriage is meaningless… love doesn’t need social sanction… we are free to love whoever falls on our path. But Osho’s views on sexual freedom were completely wasted on her. The moment she had sex with a guy, she became insecure and began seeking constant reassurance.

She demanded that he love her fully — like a wife — and lost any negotiating power she may have had, right at the start. Her lovers were frightened of her intensity, and backed off the moment they could. Avantika’s desperation mounted. “The asshole said he was too busy supervising his son’s studies to meet me, can you believe it?” or “The bugger said his wife needs him more than I do,” and so on. All her talk of detachment evaporated into thin air, and she ended up hounding the guys till they changed their telephone numbers or moved away.

Despite the feeling that I was playing with fire, I couldn’t control my euphoria at Mukesh’s text, the morning after the party: GM Hot Lady. Thanks for a great night. I called my friend Poonam and told her the whole story.

“He sounds familiar,” she countered.

“I hope it’s not the same guy another friend was telling me about — he was also a salsa dancer, a real player.”

“Must be someone else,” I said briskly, ignoring the racing of my pulse at the thought of Mukesh with other women. One part of me knew that a man like him was likely to play the field, but another tiny voice told me he was my man. He was like a drug that held out the promise of a quick high. But I was supremely confident that I wouldn’t get hooked. So far, no substance or person in my existence had made me abandon myself. What was the harm in riding the wave of attraction and letting things play out? Maybe he would make me change my mind about love and life. When Poonam called later to report that Mukesh was indeed the same guy who had broken many women’s hearts, I told her not to worry about me. “I can take care of myself,” I insisted.

The next time we met, Mukesh shared his big heartbreak story with me; the one about that life-changing, soul-crushing love affair that didn’t end like a fairytale.

“Marika was Spanish, on a visit to India,” he said.

“We were in our twenties and I was so crazy about her that I moved to Spain to be with her.”

They had a dramatic relationship that consisted of daily shouting matches and amazing make-up sex.

“The passion and anger was addictive,” he confessed.

When the inevitable breakup happened, he packed his bags and returned to India.

“I was devastated.” Despite his attempts to maintain steady, regular relationships with women, the humdrum of daily interaction bored him quickly.

“I keep trying to recreate the high I had with Marika,” he said ruefully.

Though I was discomfited by the fact that a meaningful romantic relationship was off his agenda, I felt a rush of warmth for what I convinced myself was honesty — the intimate disclosure was a measure of his trust in me, and made me feel closer to him. Also, the lure of sexual fulfillment was hard to ignore.

Maybe I hoped that being with him would help me loosen up, perhaps even adopt a more flexible view to casual sex, within the context of a loose romantic relationship. But the opportunity to take things further with Mukesh never arose. He disappeared, just as quickly as he’d appeared. I waited to hear from him, but he didn’t call. I dialled his number a few times, but our conversations were always vague.

When I suggested meeting up, he made excuses: In the middle of practice for a big event right now… Just leaving for my niece’s wedding in Pune… Laid up with the ’flu.

I struggled with feelings of rejection and a crushing awareness of my own stupidity: How could you be so delusional… Everyone told you about him… What’s wrong with you…?

The disparity between his world and mine was obvious, and I wondered why I’d imagined they could ever merge. The stories I told myself about Mukesh’s change of heart varied though, depending on my mood. I told Poonam that I regretted playing hard to get; that I should have been more brazen about my willingness to get intimate with him, in time.

But the true story was the hardest to tell: that Mukesh was used to dancing his way quickly into women’s beds; that he didn’t like to wait; and that he wasn’t interested in a relationship with me. For men like him, love was only about the chase. Once they got to the finish line, things were over.

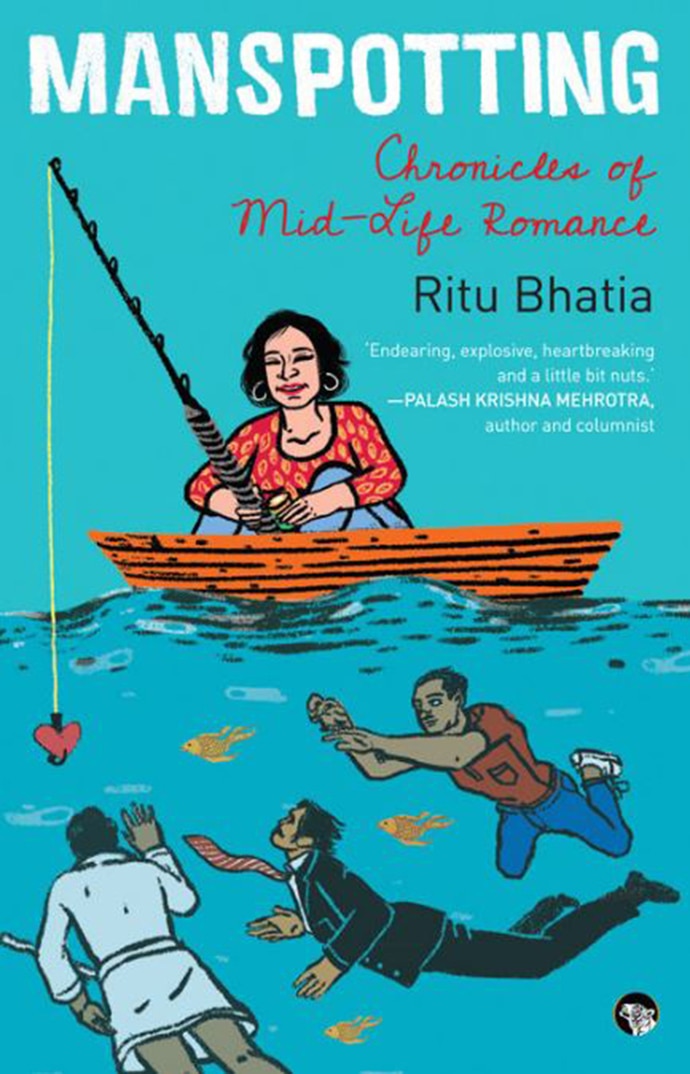

(Excerpted with permissions of Speaking Tiger Books from Manspotting by Ritu Bhatia.)