Why I think modern Hindi literature looks woefully poor before Urdu

As the season of literature festivals takes off in India, I am reminded of an encounter of the literary kind in my own life. Shortly after I was appointed a Judge of the Allahabad High Court in 1991, a friend of mine, a Hindi writer named Neelkant, came to my residence and requested me to be the chief guest at a function in the Hindustani Academy (next to the Prayag Sangeet Samiti), at which a book he had written, on some aspects of Hindi literature, would be released.

Ordinarily, after becoming a Judge, I would not attend social functions as my seniors in the Indian judiciary had advised me that a Judge must live a reclusive life. But then, there can be exceptions. Neelkant was such a dear friend (the last I heard of him was that he was living in Jhunsi, on the other side of the Ganges) that I could not refuse.

There was a big crowd at the Hindustani Academy hall that day (it was probably in early 1992). Many speakers spoke, and then I was asked to speak.

I have been outspoken throughout my life — and this occasion was to be no exception. I said that though I had a high opinion of medieval Hindi writers like Kabir, Sur, Tulsi, Rahim, Raskhan, Mira, etc, modern Hindi literature was mostly sub-standard. In fact, I remember I used the words 'daridra' and 'ghatiya') and had no place in world literature.

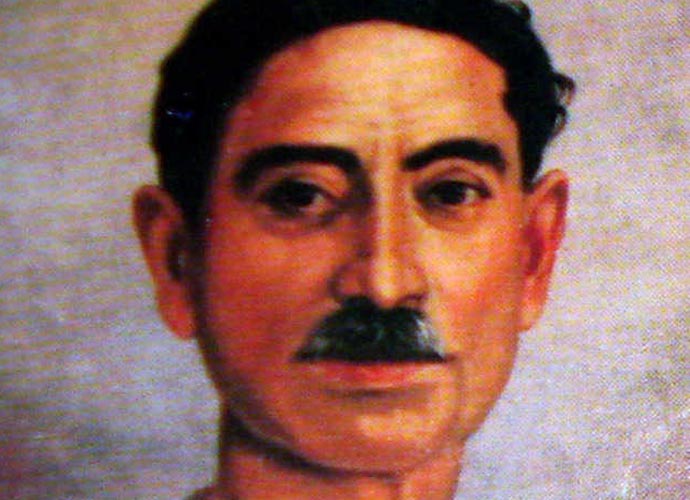

The really great modern lndian literature, I said, was in Urdu in poetry and Bangla in prose. I especially praised Urdu poets like Mir, Ghalib, Faiz, Firaq, etc. Even among the modern Hindi writers, the best acclaimed were those with an Urdu background, like Premchand, Kishan Chand, Rajinder Singh Bedi, etc.

When I was saying all this, hooting against me started. One Hindi writer stood up and in a loud voice, asked, "Aap yahan kyon aaye? Aise anpadh admi ko kisne Judge bana diya?" ('Why have you come here? Who has made such an illiterate man a Judge?").

I replied that I had come because I had been invited by the writer of the book which was being released. I also said that if some people did not agree with me, they could coolly and politely say that I was mistaken, and they could point out the good things in modern Hindi literature. I said I had an open mind; it may be the case that I might have a wrong impression of modern Hindi literature, and if convinced, I could change my opinion about it. But is this the way educated people should express their disagreement with me?

But this only further infuriated the motley crowd of Hindi writers and self-proclaimed 'literati' — and the uproar against me increased.

When I could not take these insults any more, I walked out of the hall, saying, "You are all a bunch of goondas."

The next day, the newspapers, both Hindi and English, were full of this incident, and the result was that this gave the book such publicity, all copies of Neelkant's book were immediately sold out - and many more editions were in great demand.

Neelkant later came to my house and apologised for the misbehaviour of people in the crowd, but I told him not to worry. He should write another book on some aspects of Hindi literature, I suggested, and again call me as chief guest to the function for its release. I would again call modern Hindi literature 'daridra' and 'ghatiya', which would result in another uproar, and the resultant publicity would again ensure a good sale of the book!

The truth is, and I know this will be unpalatable to many, Hindi is not the people's language. The people's language, in large parts of India, is Hindustani or khari boli. The difference between Hindi and Hindustani can be illustrated by giving an example. In Hindustani, we say, "Udhar dekhiye" (look there). In Hindi, we say, "Udhar avlokan keejiye". While speaking, the common man never says, "Udhar avlokan keejiye".

Hindi is a literary, artificially created language.

In fact, till 1947, Urdu was the common language of the educated class, whether Hindu, Muslim or Sikh, in large parts of India. Hindi was created as part of the British divide and rule policy, by propagating that Hindi was the language of Hindus, while Urdu was the language of Muslims, and by hatefully replacing Persian and Arabic words which had become of common usage in Hindustani, with Sanskrit words. Thus, 'zila' was replaced by 'janpad'.

When I was a judge in the Allahabad High Court, a lawyer, who would always argue in Hindi, appeared before me one day with a petition titled 'Pratibhu Avedan Patra'. I asked the lawyer what 'Pratibhu' meant. He said it meant bail. I said he should have used the word bail or 'zamaanat' instead, which everyone understands, instead of 'Pratibhu' which no one understands.

Urdu is still loved by the people of India (see my articles 'What is Urdu' and 'Great injustice to Urdu in India' online and on my blog Satyam Bruyat). The poetry books of Ghalib, Faiz, Firaq, Josh, etc., (nowadays often in the Devanagari script) are bought and widely read by people, whereas no one reads books by Hindi writers like Jaishankar Prasad, Sumitranandan Pant or Mahadevi Verma. Massive crowds come to 'mushairas' as well.

The truth is that Hindi does not have the sophistication and 'dum' in it, which Urdu does.