Why it's important to temper the 'greatness' of VS Naipaul with a dose of reality

"Life goes on, the past continues. After conquests and destruction, the past simply reasserts itself." These are lines that I found highlighted in my second-hand copy of India: A Wounded Civilization, one of only two VS Naipaul books that I own now, the other being Miguel Street. Over the last decade at least four more Naipaul titles have been given away, lent-and-never-retrieved or generally confined to the diffuse grey zone of memory where unwanted books go to die. It's safe to say that I don't see myself rereading much of Sir Vidia (or Pablo Neruda or any of the other men I read a fair bit of in college, before they turned out to be rapists and serial abusers and so on).

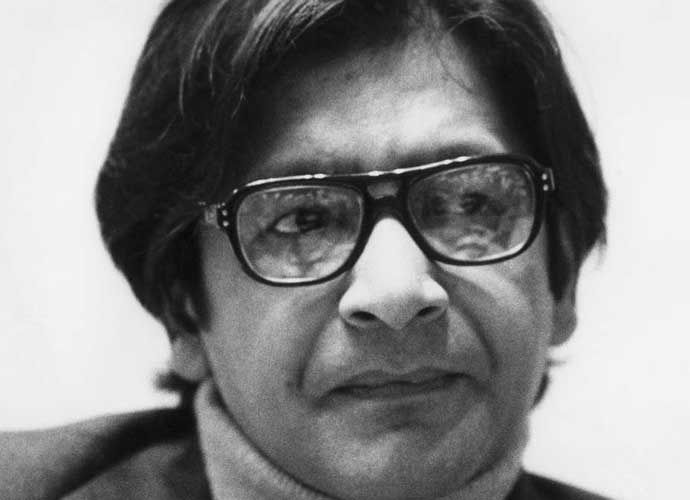

This is why these lines feel significant today, when there will be much ready-reckoning of his life and works — because when you sift through the 20-odd books, the many deranged tirades against (in no particular order) Islam, women, working-class people; when you're done sifting through those expertly crafted sentences, you'll end up with a bitter man stuck in the past. In Naipaul's worlds, both fictional and documented, the past maintains a quite impenetrable chokehold on the human psyche, which is really just a fancy way of justifying bigotry and resistance to change.

As has been well-documented in biographies authorised and otherwise, Naipaul abused the women in his life (Patricia Hale, Margaret Gooding) physically and mentally, and later tried to airbrush these decades of cruelty. Even in Naipaul's admission that his sadism led Patricia, his wife of 41 years to her grave, he sounded almost begrudging. His views on Austen and female novelists in general were laughable and not worth the effort of rebuttal. He wrote hundreds of thousands of words elaborating the 'barbarism' of Islam... and dedicated perhaps his most odious, Islamophobic book to his Pakistani Muslim wife. Whichever way you cut it these are great reasons to temper Naipaul's 'greatness' with a dose of reality.

What then is worth holding on to? His early work remains, to my mind, the stuff that retains the most relevance today — In a Free State, a few crystalline comedies from Miguel Street and of course, A House for Mr Biswas. These fictions are the ones least affected by the politics that overwhelmed his later novels, like the fearmongering, horridly overwritten Guerrillas (so obviously written for an audience of disenchanted 1960s white liberals) and the tedious Willie Chandran books. And they're great examples of his comedic talents, his ear for farce.

In Miguel Street, especially, there are some brilliant sketches of the Trinidadian Indian community, helped along with smatterings of calypso music, cricket and the rapid-fire delivery of Trinidadian English. But even more so than all of these factors, this is a book that rewards slow reading (although it's quite fast-paced and structurally accessible) in the way more and more of the neighbourhood is revealed with each story's unravelling.

"A stranger could drive through Miguel Street and just say 'Sum!' because he could see no more. But we who lived there saw our street as a world, where everybody was quite different from everybody else. Mam-man was mad; George was stupid; Big Foot was a bully; Hat was an adventurer; Popo was a philosopher; and Morgan was our comedian."

In 1971, Naipaul was awarded the Booker for In a Free State. As Edward Said, Doris Lessing and others have pointed out, Naipaul — and this is especially true for everything he wrote post In a Free State — transformed failures of basic empathy (to comprehend Islam as something other than a monolith, to comprehend that women could be his literary equals or gasp, superiors) into a kind of twisted intellectual performance.

And although Naipaul was very much a creature of a bygone era, this is a trait that we must talk about right now because it is back in vogue in a big way. Just look at the church of Saint Elon or the corners of the Internet beholden to the likes of Jordan Peterson or Richard Dawkins. While the political faces of bigotry around the world today seem cartoonish and crude they are backed by a philosophy of hatred that's becoming a little more normalised every day.

May I be so bold as to offer a correctional rewriting of Naipaul's most famous lines? The world is what it is only because we allow it. And men who don't see this are worth nothing; they will end up becoming nothing.