How Indian pop culture fetishises the maid

I recently saw the cover of a new novel, Maidless in Mumbai. At the centre of the frame is a beleaguered young woman, very obviously dressed for a corporate job with her handbag, dangling precariously from her left shoulder. Her laundry is in a mess, an iron lies unplugged and the books in her arms will fall to the ground any moment now. We are told that her only dream is to find the “perfect maid” to live forever with. Above the title of the book is a happy-looking domestic help — reclining, fanning herself like a zamindar, gently, calmly.

It’s role-reversal via body language. Surely the author and the designer could not have foreseen the events at Mahagun Moderne, Noida, but the caricature on the cover looks an awful lot like “punching down”, that is, making a joke at the expense of someone less-privileged than you are.

The residents at Mahugun Moderne had come together to banish the protests led by domestic workers of that area. Many had tweeted that it was a violent havoc created by illegal migrants from smaller towns who had occupied their space. Whichever side of this dispute you might be on, the story of maids demanding a raise like Zohra Bibi doesn’t end here. Visual pop culture remains a constant reminder that domestic labourers have been mocked and ridiculed multiple times over the years.

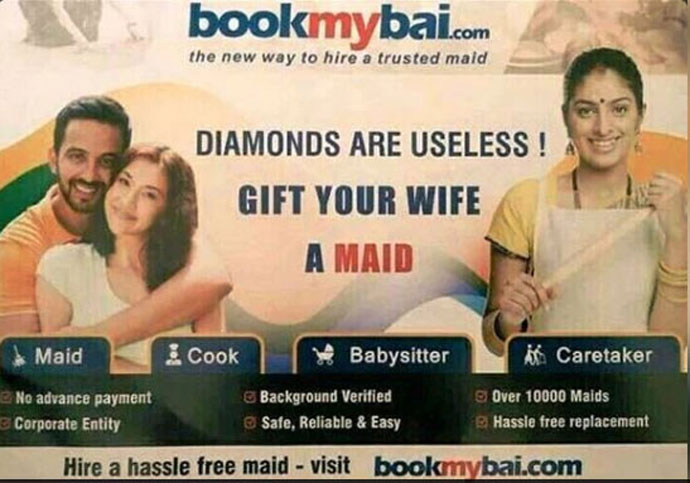

Last year, there was an advertisement for Bookmybai.com which sparked off a controversy, rightfully so, as its tagline stated, “Diamonds are useless! This Valentine’s day, gift your wife a maid".

Not only did it equate jewellery and women in a single breath, it was easily mistaken as a genuine boon for "working" women. Another example: regular viewers of Channel V would recall a filler between consecutive programmes curtly named “Brought to you Bai”. The bai walks gracefully with her broom and mop; her catch phrase is “itna paisa mein itnaich milenga (this is all that you get for that amount of money)".

Let's not pretend that there is no narrative to these representations. Let’s also not forget the dirty jokes that have become a part of roadside gossips post the Shiney Ahuja incident. In 2011, a micromax ad decided to play around this unfortunate event by giving more fodder for mockery. It showed a young girl exclaiming, “Shiney bought me a new 'Bling' (mobile phone)”. She is joined by few others who utter the same sentence. These casual phrases meant to tickle the audience go a long way in adding up to the centuries of oppression that lie at the core of recruiting domestic labour.

Almost a class war it looks like pic.twitter.com/BVI9jxEh7d

— Ashish (@AshishXL) July 12, 2017

For a large number of upper middle classes and now increasingly lower-middle classes too, there is a rampant belief that education and a decent job is the end of the world. If one achieves these two, there is never any need for them to worry about anything else. Including one’s basic chores, for one will always have the money to hire labour. This pattern, I believe, is the root of all misery, the idea that a class is always going to sustain you and do your dirty laundry while you can go out for your respective jobs and get handsomely paid.

It gets worse when one looks at how even this is a gendered process. While the men are conditioned from a very early age that household work is the woman’s job, for women, the pile of extra work just keeps on increasing. Whether she outsources it, or does it herself, this is mostly unremunerated/lowly paid labour we are speaking of. Underneath this rift, lies a fundamental question as to why domestic labour be considered an “unskilled” department (hence underpaid).

Why is domestic labour labelled as an “unskilled” industry whereas working in a publishing company is not?

Moreover, why are we raising children in a delusion that their shit will always get done magically, and that they only need to have enough money for the same?

The other serious problem lies in how males in the households are depicted to fantasise maids in popular culture. In 2016, there was a hugely viral web-series called Maid In India feeding into urban and male fantasies of the "ideal maid".

Like the cover in Maidless in Mumbai, here too, the conflict between the woman heading the household and the maid is rather interesting. The maid here is portrayed as “high class”, demanding high salary and giving free fashion advice. Her male employer is immediately shown to be smitten by her and quickly neglects his wife (due to her weight gain etc).

Eventually, the maid ends up giving his wife the ultimate lesson (which if you watch carefully, is the husband speaking through her). She mansplains in length about how women must work indoors to keep themselves attractive like her. A very common trope in India — we sexualise maids and silence them, so much so that whatever little they speak onscreen is actually the dominant male voice.

These fantasies fulfil three objectives:

a) the urban male is allowed to be a douche when it comes to doing chores.

b) It normalises crimes of abuse and molestation that are inflicted upon maids.

c) It de-humanises domestic labourers, they become objects, whom we can mould at will. The bai is a hyper-sexualised member of the working class, vis-a-vis notions of "ownership" and reinforcing the master-servant hierarchy, both sexually and otherwise. In a popular song, “Aye Hip Hopper”, Ishq Bector addresses the servitude fetish directly:

God she thinks she’s hot like Rekha

Maybe but she’s not my flavour

Love in here is too much labour

Labour, L-labour

How can I? I am a star hip hopper

She’s my bai-just a part time naukar

These representations of domestic workers tell us that future Mahagun Modernes are waiting to happen. These women are not, as Ishq Bector suggests, sultry vixens, or — as the cover of Maidless in Mumbai would have us believe — "kaamchor" lazybones grown fat and complacent on the goodwill of their benevolent employers. They have the right to organise themselves to protest against the hollow foundations that middle class India is known to blossom in.

They're human beings, who deserve to be treated with respect. For those who won’t do your chores despite being healthy (I’m judging you), the least you can do is to behave well in front of your domestic workers.

Is that too much to ask?