Why the number of minorities in jails is rising in India

Even days after a cleric and his relatives were assaulted and stabbed in the Baghpat district of Uttar Pradesh, the state police have not been able to make a single arrest. A news daily has, meanwhile, quoted a police official as saying, "There may have been a trigger." The official was perhaps implying that the victims brought it upon themselves.

Earlier, Pehlu Khan and Umar Khan, two dairy farmers from the Meo community who were lynched, were also blamed for their own murders. The charges against them were eating beef and "smuggling" cows, respectively. Cases were filed against them and those accompanying them and their family members. Some of them were also beaten but were lucky enough to escape death.

These cases make one wonder if Indian society is fast turning hostile towards the second-largest community of the country that comprises 14.2 per cent (172 million) of the total population? Put differently, is India's democracy "penal" and "punitive" towards its minorities?

Hostile to minorities

A new collaborative study by Germany-based anthropologist and Australia-based economist argues, with the help of hard data, that India indeed is "unfriendly, if not hostile" to its minorities, including Dalits and Adivasis, explained by their disproportionately higher number in jails. They also stress that in this respect, India is no different from most democracies, including those in the West.

Professor Irfan Ahmad, senior research fellow at Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity, Germany and Dr Md Zakaria Siddiqui, research fellow at the Institute for Economics and Peace, Australia published a paper in the reputed Economic and Political Weekly (EPW) in November 2017. Titled, Democracy in Jail, the paper elaborates on "(the) over-representation of minorities in Indian prisons" using government data and comparing them with other countries.

The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) annually releases reports on Prison Statistics India (PSI) that figure on the inside pages of newspapers only to be conveniently forgotten for the rest of the year. Prisoners have attracted scant attention from even academics in India, and those who have focussed on their collective plight and violation of their rights. Only a few have actually delved into the caste or religious identities of prisoners.

Through their EPW essay, the two authors seek to fill this gap. They analysed the PSI data for the last 16y ears and contrasted it with the census data to show how "minorities stand over-represented in prisons in most states of India. Gujarat and Maharashtra have a higher representation of all minorities in their prisons".

In India, we talk of minorities mostly in religious terms (and recently sexual orientation). Ahmad and Zakaria, however, use the term "minority" to include all oppressed groups with "lack of access to, and the exercise of political power". Thus, besides religious minorities, Dalits and Adivasis too have been counted as "minorities" in this study, a shift from the mainstream politics of Dalits, who regards themselves as bahujan or majority.

An interesting inference they draw is that it is not just Dalits (16.63 per cent of the total population), Adivasis (8.63 per cent) and Muslims (14.23 per cent), who are disproportionately higher in prisons in comparison to their respective populations, but even Hindus are over-represented in states such as Nagaland, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Jammu & Kashmir, etc, where they are in a minority.

Ahmad and Siddiqui note that seven out of every 10 prisoners are undertrails or detenues and that three quarters of Muslim prisoners are "non convicts". In fact, in Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Delhi, more than 80 per cent Muslim prisoners are non convicts, they point out. They acknowledge this limitation when they write that they "cannot conclusively establish the precise cause of over-representation of minorities in prisons," but point out that the PSI data "possibly offers a clue".

The study also makes an interesting point that if Indian democracy is punitive, penal or punishing, it is very much in line with western democracies where too minorities are over-represented, whether they are Blacks and Hispanics in the US, Muslims and Blacks in the UK, Muslims (of African and Arab origin) in France, or Aboriginals in Canada and Australia.

Democracy in jail

Ahmad and Siddiqui also connect national-level data with lived experiences of two prisoners who were arrested on terror-related charges, but were acquitted by different courts. They discuss their "prison memoirs" that they subsequently wrote - Md Aamir Khan after 14 years and Mufti Qayyum after 11 years in jail. This makes the study gripping, especially the point about a unique kind of "democracy in prison" where "…sharing in a space of un-freedom and in a state marked by helplessness generated an unusual bond amongst prisoners".

They write, "Democracy emanating from identification with, and the sharing of suffering, pain, human finitude, and vulnerability seems to be at radical variance with the lethal injustice and callousness of the rationalised bureaucracy, and institutions sanctioned by democracy as a state system manifest in the periodic spectacle of elections."

Prejudices against minorities

Deeply-entrenched prejudices against minorities, Dalits and Adivasis, no doubt, play an important role in their harassment and incarceration. A recent case at Aliah University, where I teach, seems to point toward this direction. Due to the high-headedness of the university administration and senior bureaucrats, few students of my university were sent to jail for over a week on charges of staging dharna and allegedly obstructing government officials from discharging their duties. These students later narrated how some jail inmates called them terrorists simply because they had Muslim names and some of them sported beards.

Hundreds of Muslim youths have been rotting in several jails on terror related charges, although few lucky ones such as Khan and Qayyum could manage to exit jails, after spending precious years of their lives in prisons. Not all cases pertain to terror though and it would thus not be fair to infer from the PSI data that straightjacket biases against them are the sole reason, although they are no less critical.

In a recent incident in the national capital region, when a young school student of Ryan International was murdered, the first suspect was the bus conductor, who said he was hung upside down, beaten, and forced to falsely confess. Similarly, tribal rights activist Soni Sori had to suffer at the hands of Chhattisgarh police. If you are poor or come from the marginalised section, you become an easy prey. Lethargic judicial system is another critical factor due to which justice is often delayed, if not denied.

Normalising crime against minorities

Institutions are reflections of the society. Whether police or judiciary - particularly the lower judiciary - all of them represent the mindset that pervades in society. When the most heated debates in the country revolve around "villainies" of Babur, Aurangzeb, Alauddin Khilji, Tipu Sultan, etc, the target of course is not those who died centuries ago, but contemporary Muslims deemed as successors of those "invaders".

Ahmad and Siddiqui focused on PSI data to argue about the "punitive" nature of the institutions in the country, but what is more troublesome is that hate crimes against Muslims in particular and other minorities in general seem to have become normalised. Communal riots, fake encounters, and lynching of Muslims in the name of cow-vigilantism may lead to an uproar in certain sections, but the perpetrators mostly go unpunished.

Poor representations of minorities in government institutions

The problem is further aggravated by the fact that while in jails, minority communities, particularly Muslims, are over-represented - in other government institutions from elected representatives to police forces and judiciary their representation is abysmally low.

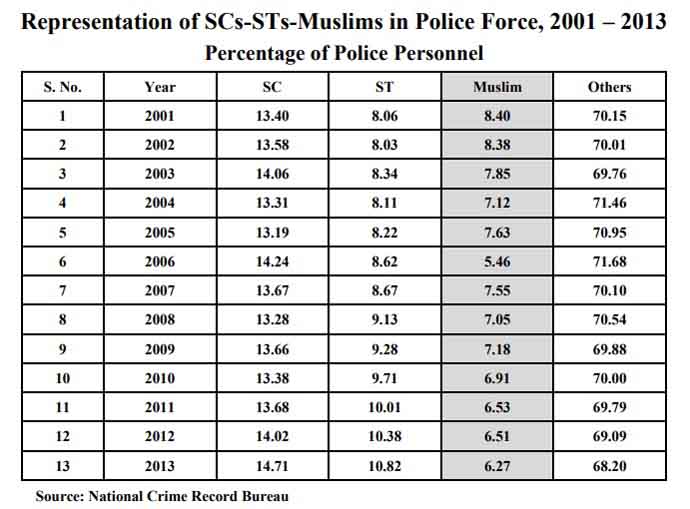

According to 2013 data of NCRB (the government has since stopped giving religion-wise data), only 6.27 per cent of country's police personnel were Muslims. The percentage further goes down as the rank goes up. It is interesting to note here that according to data collected by IOS, their numbers had strangely continued to dwindle from 2001 onwards when it was 8.40 per cent.

Reservation policies of the government have considerably helped the SC and ST communities, who were 14.71 per cent and 10.82 per cent, respectively, in police force, as of 2013. But the dominance of upper castes in decision-making positions as well as institutional biases has largely continued.

Ahmad and Siddiqui cite the example of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, who was in jail for more than 10 years. From Azad's era of freedom-struggle to the present times, what has changed though is the perception of Indians from "we are ready to go to jail" to "put them in jail". This shift in perception, suggest the authors, perpetuates the victimisation of minorities evident in their disproportionate representation in jails.