Evicting 'Nehru' from the Nehru Memorial

The White House never became a museum in memory of George Washington. At the Kremlin, only Lenin’s private rooms were thrown open to the public. The rest of the Kremlin continued to perform its official functions, including providing accommodation to Lenin’s successors. In Beijing, Mao Zedong’s home within Zhongnanhai, next to the Forbidden City, was never converted into a museum. And 10 Downing Street has remained the British Prime Minister’s home since 1732. Why then did the official residence of the first Indian PM become a museum?

The decision of the authorities at the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML) — to extend the scope of the memorial from projecting only the life of the first PM to including the contribution of all PMs — has generated expected controversy along predictable lines. While those who have a special place in their hearts and minds for Jawaharlal Nehru do not wish to see any dilution in the kind of homage paid to him, others believe that the contribution of his successors ought to be also recognised.

The focus of the controversy has been on whether such a museum for all Prime Ministers should be housed within the premises of the NMML or outside.

However, several other issues worth raising have not been addressed.

The question may well be asked as to whether it is at all worth celebrating the contribution of all Prime Ministers.

I am not aware of any major country around the world that has such a museum in memory of every single head of government. I would not hesitate to assert that so far, only five prime ministers have as yet earned their place in history — Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi, PV Narasimha Rao, Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh. Nehru did shape modern India, strengthening the foundations of a nascent Republic. Indira Gandhi left her mark on economic and social policy as well as on regional security. Narasimha Rao provided political leadership at a particularly stressful time in recent history and altered the direction and pace of the Indian economy. Atal Bihari Vajpayee not only declared India a nuclear weapons power but took important economic and foreign policy initiatives that defined India over the next decade. Manmohan Singh presided over an economy that grew at unprecedented rates, contributing to a sharp decline in poverty, and altered the course of Indian foreign policy with the nuclear deal he signed with the United States.

Perhaps one could consider the name of Lal Bahadur Shastri, for his leadership during war.

None of the others have left their mark in a manner that deserves a mention in a museum.

The jury is out on Prime Minister Narendra Modi. If he returns to office in 2019 and distinguishes himself in his second term, he would certainly qualify. However, given India’s fractious and populist politics, no government-funded museum will risk not mentioning all Prime Ministers. Thus, even Gulzari Lal Nanda will get a mention.

A more fundamental question that is worth examining is why in the first place, Teen Murti House became the Prime Minister’s official residence, and, secondly, who took the decision, and why, to convert this into a museum.

It is worth remembering that Nehru decided to lay claim to the official residence of the Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Armed Forces (which is what Teen Murti House was till August 1948) only after Mahatma Gandhi’s death and a year into his tenure. Till then, he lived in a regular Lutyens’ bungalow on what is now Motilal Nehru Marg, like all his cabinet colleagues including Sardar Patel.

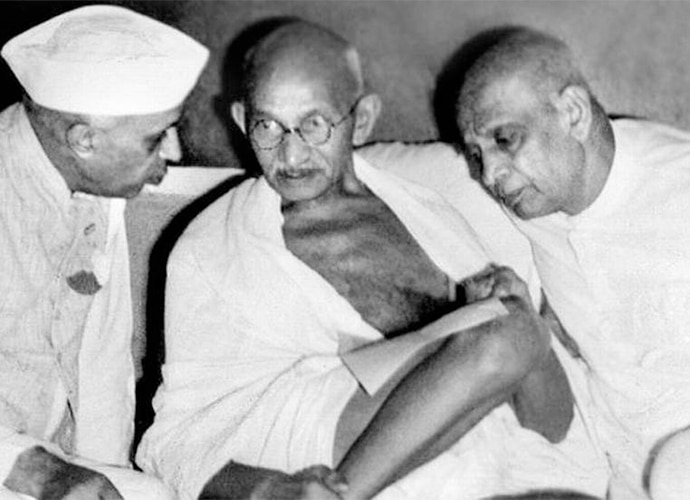

In 1947, Nehru was, after all, only one among equals. He had to demonstrate to the Mahatma, who chose him for the job, that the Prime Minister-ship had not gone to his head. A majority of the leadership of the Congress Party in fact wanted Sardar Patel to be named Prime Minister. Gandhiji overruled them and named Nehru.

Once the Mahatma was gone, Nehru would have felt liberated enough to move into the grand palace of the Commander-in-Chief, located a stone’s throw from the Viceroy’s palace – Rashtrapati Bhavan.

Nehru’s decision to live in Teen Murti House was perhaps also an attempt to elevate himself above the rest of the Congress leadership in the public eye. From primus inter pares (first among equals), Nehru made himself numero uno.

Now to the question as to how the Prime Minister’s house became a museum. After all, no one thought of making 1, Aurangzeb (Abdul Kalam) Road a museum for Sardar Patel when he died in 1950. It was Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, as President, MC Chagla, as minister for education and culture, and Indira Gandhi as minister for information and broadcasting, who took the decision, with several others supporting them, to convert Teen Murti House into the Nehru Museum.

I am not aware if any political scientist or historian has examined the question as to why Lal Bahadur Shastri did not move into what was the official residence of the Prime Minister. Perhaps he did not have the gumption to do so.

In the United States, the memory of its first President, George Washington, is celebrated in a museum housed in Washington’s own home at Mount Vernon. Surely, the Nehru family home in Allahabad could have been made the Nehru museum. But it appears such thinking did not prevail within Delhi’s corridors of power at the time — it seems without doubt that the Nehruvians who survived Nehru did not want any future prime minister to live in the impressive and regal surroundings of the estate of the Imperial Commander-in-Chief.

The current debate about the future of Teen Murti House and the NMML offers an opportunity to examine the past and see whether the original decision was in fact the correct decision. The political response would be along partisan lines. However, one hopes that there are enough number of professional historians and political scientists — not blindly partisan — who would be willing to examine this issue afresh and express their opinion.