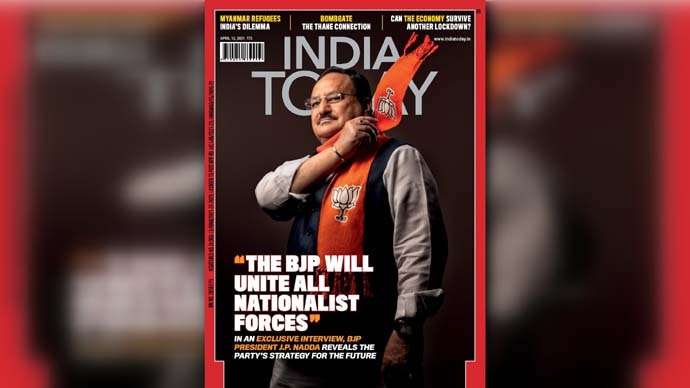

"The BJP will unify all nationalist forces"

India Today Editor-in-Chief speaks about the exclusive interview with BJP chief JP Nadda and how the party intends to use nationalism rather than Hindutva as its future strategy, in the April 12, 2021 edition of the India Today Magazine.

One of India’s tectonic political shifts has been the metamorphosis of the BJP from the principal opposition grouping to the world’s largest party, which claims to have a membership of over 150 million. This change was heralded by the arrival of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his party chief Amit Shah on the national scene in 2014.

In the past seven years, the BJP has transformed itself into a relentless election fighting machine that seems to be in perpetual campaign mode. This complex organism extends from the heights of national government down to grassroots units such as booth committees earlier to ‘page committees’ that mobilise voters and cadre, and is constantly being refined. The creation and successful management of such a massive organisation is a stupendous managerial feat, worthy of study by the Harvard Business School. The party has a clear strategy as it fights state and even municipal elections with the same zeal as it does the general elections. It is in power in eight states on its own and in alliance in nine others, governing 48 per cent of India’s landmass.

Election verdicts do not mark the end of its quest for power. In Madhya Pradesh, Haryana and Goa, the party fell short of a majority but formed governments through coalitions or luring representatives from other parties. The Congress government in Rajasthan survived a close call last year. In Puducherry, the BJP is believed to be behind the Narayanasamy government’s fall just a few weeks before its term ended. No Opposition-ruled state is safe, especially when it is up against an organisation that never sleeps, never gives up and believes that politics is a 24x7, 365-day calling. It’s fair to say that India has never seen another national party as aggressive and well-organised as BJP 2.0.

Last January, Shah, who deserves most of the credit for creating this formidable poll fighting machine, handed the baton of BJP chief to Jagat Prakash Nadda, a party insider. Nadda has worked with Modi and Shah since 1998 and was, in fact, tipped to succeed Rajnath Singh as party president in 2013. The calm, amiable and methodical leader has been groomed for this post, acting as working president since June 2019. He has big shoes to fill. In the 14 months that he has been party chief, Nadda has overseen the Bihar election, where the BJP not just formed a coalition government but, for the first time, surpassed alliance partner JD(U)’s tally.

The new chief is already in the thick of his biggest challenge yet—steering the party through elections in four of the seven states that form part of the BJP’s ‘Coromandel Strategy’—the plan to establish a presence in a contiguous territorial swathe from Kerala in the south to West Bengal in the east. First highlighted by Shah in 2016, this region is where the BJP has a minimal political footprint. It is a final frontier, one the party will need to breach before claiming to have a pan-Indian presence, displacing any memories of the Congress in its heyday. Its biggest impediment in the project is the fact that it is regarded as a north Indian party and that Prime Minister Modi has limited appeal in several southern states. Therefore, the assembly elections in Tamil Nadu and Kerala assume a larger significance in its long-term strategy. So far, it remains a marginal player in these states.

For our current issue, Group Editorial Director (Publishing) Raj Chengappa and Senior Editor Anilesh S Mahajan caught up with Nadda for his most detailed interview yet. The candid, self-assured and disciplined Nadda not only described his party’s current strategy but also outlined its future game plan. That plan, in a nutshell, is to aim for continuity, consolidation and scaling up. This strategy is evident in states like Telangana, where the BJP has displaced the Congress as the largest opposition party. It will be seen in states where the party faces key electoral battles in the months ahead: Uttar Pradesh, Punjab and Gujarat in 2022; Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh in 2023, before the 2024 general election. As Nadda emphasises, the BJP fights every election to win. Among the major imperatives that emerged in the interview was how his party intends to use nationalism rather than Hindutva as its future strategy, providing us with the cover line: ‘The BJP will unify all nationalist forces’. It’s a clever strategy. Nationalism has a far more pan-Indian appeal than Hindutva, especially in the south, where the BJP is viewed with suspicion. Armed with a long-term vision, the party plans to use Brand Modi to achieve most of its political goals. Nadda says as much, with all the air of a brand manager: “It is the party’s responsibility to best utilise his services for the poll campaign.”

That said, Modi-itis, or the party’s excessive reliance on the prime minister for every election, also runs the risk of not nurturing local leadership. Great parties have taken great falls because of this oversight. The decline of the Congress, it must be remembered, began with their over-reliance on Brand Gandhi and its marginalisation of charismatic regional leaders. The BJP strategy will face its biggest test in the West Bengal election. If it wins, it will try and replicate the formula in other states where it lacks a presence. If it doesn’t win, it will need to return to the drawing board to recast its strategy and rework its electoral arithmetic for the elections ahead. This is a given from what we know of the BJP and its relentless big-picture vision so far. Pausing is never an option.