What Pitaji told me about Bhagat Singh, Gandhi, Nehru and Netaji

My grandfather always said, "Don't stress about your exam; I never did too well in mine either." Later in life I learnt, it can be pretty tough to score top marks while fighting for your country's independence. Pitaji, as we called him, gave his BA examinations from jail with an armed guard standing outside the room and was barely released in time for his MA finals.

Everyone's grandparents are special, mine were no different but perhaps my grandfather's stories were just that little bit unique. He was 18, when the British first arrested him for conspiring in the high-profile killing of police officer Saunders for which Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru were eventually hanged. At the time, he was one of the six people who were detained from all over the country under the Tough (Act) Regulation 3 of 1818, Mahatma Gandhi and Subhas Chandra Bose being two others.

So, it was perhaps destiny that three years later he would find himself in the same Lahore Central Jail, which turned out to be the final home for the three freedom fighters on death row. What he saw there and came to know, perhaps even history books aren't aware of still.

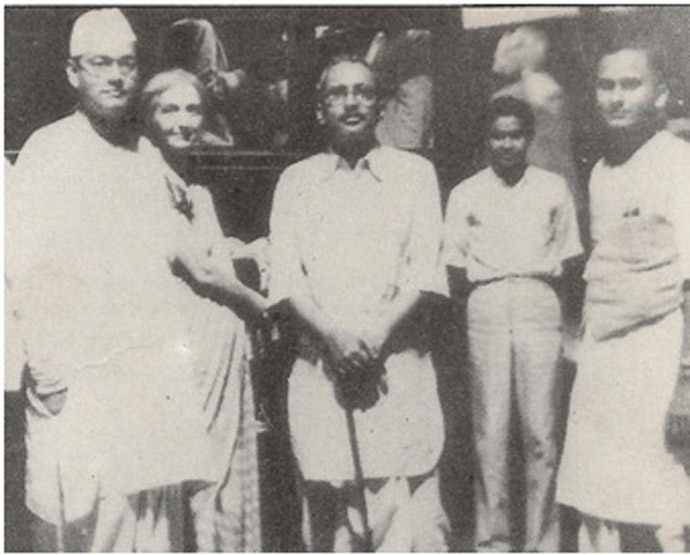

|

| The writer's grandfather. |

Bhagat Singh and my grandfather communicated through Barkat, a barber. On March 23, 1931, Barkat came running to Pitaji and said, "Sardarji says instead of tomorrow, the execution will take place this evening". With public emotions running high against the imminent hangings, the British had decided to secretly prepone the executions. Pitaji sent the barber back to Bhagat Singh asking him to confirm; the comb that the legendary freedom fighter sent back as a final gesture was engraved with his name.

My grandfather described that day in Lahore Jail as something that would probably send shivers down your spine, even today. All inmates used to be locked up in their cells every evening by 7pm, but that evening they were asked to go indoors much earlier. The jail warden was not allowed to talk, but he broke down and his tears spoke a thousand words. No one ate that night and when the three freedom fighters walked out of their cells with their heads held high, the great prison resonated with slogans.

Pitaji was a moderate revolutionary but his first arrest built him a formidable reputation, so that every time the British went looking for a scapegoat, his name topped their list. By the time he was 22, he had been jailed seven times already. Whenever he returned home, my great-grandfather, who was one of the most respected newspaper editors in Lahore, would ask resignedly, "How many days are you home for this time?"

I'm reminded of an incident where my grandfather and his aides had planned to assassinate the then Punjab governor, Sir Geoffrey, at the annual convocation of Lahore's Punjab University. Dr S Radhakrishnan, the second president of India, also happened to be sharing the same stage. Years later, the president would laugh about the events, saying "My luck saved me otherwise, I don't know where the bullets fired by you fellows would have hit," he said.

The lack of expertise among these young, driven men meant sometimes they got the wrong man, like in the Saunders case. But the intent was pure. They were only driven by their vision and firmly followed Bhagat Singh's idea of full independence for India: "Human blood is sacred. Our attack is against an institution, not an individual".

With the revolutionary momentum slowly dying down after the notorious triple hanging, my grandfather joined the family Urdu newspaper Pratap in Lahore. Here, one of his earliest memories as a journalist was receiving a postcard from Mahatma Gandhi in Yerwada Jail. This was also the time when he came in contact with Jawaharlal Nehru.

|

| Mahatma Gandhi's letter to the writer's grandfather. |

But perhaps the person who understood the revolutionaries the most was Subhas Chandra Bose. Netaji was someone who acknowledged that non-violence was a means, but not a principle of faith, something that eventually led to his parting of ways from Gandhi. My grandfather was lucky to meet Netaji a few times.

It was during one such meeting in 1931 that Netaji told him that he wanted the Congress and revolutionaries to work together. Later, they exchanged several letters but avoided discussing anything political as they were under watch.

|

| With Netaji. |

In fact, for years my grandfather could not step out of his house without being trailed by the CID, who had also ransacked his office. He used to make light of things and say that if anyone wanted to know how many revolutionaries are under a roof, all they needed to was count the men from the "secret services" outside.

The last time Pitaji was in jail, he became acquainted with one of the rising political leaders, Biju Patnaik, who later became Odisha's chief minister. He was released from prison in the summer of 1945.

|

| The writer's grandfather with Jawaharlal Nehru. |

During the Emergency, he refused to lay low and fought back hard against the paralysis that crippled the Indian democracy, even when several attempts were made on his life. He was also a prime target for Khalistani terrorists who tried many a time to assassinate him during the volatile era of militancy in Punjab.

Pitaji didn't know how to compromise on his ideals. During the independence struggle, he shared his surname with another freedom fighter who turned approver in the Bhagat Singh case. Since that day, my grandfather was known only by his first name, Virendra.

He always encouraged us to read and write but not just from textbooks. He was ecstatic when my first story was published in a newspaper. He would give me Rs 500 in every few weeks but with the condition that the money would only be used to buy newspapers. The last time he sent me some money was when I was studying in Delhi and decided to thank him personally later when I got home.

I still have all that money: untouched and tucked away safely. It is a loving reminder of the piece of history that I grew up with. There was so much more I wanted to know from him. But time waits for no one.