For John Berger, in the beginning was the gaze

As the myth goes: In the beginning was the word. For John Berger, it could very well be, In the beginning was The Gaze.

"Seeing comes before words,” he wrote, in that little classic with images and paintings in the book form, Ways of Seeing which has stayed and sustained its "inner gaze", despite the world being clouded by countless wars, devastations, movements and freedoms, mass displacement and exile.

“The child looks and recognises before it can speak. But there is also another sense in which seeing comes before words. It is seeing which establishes our place in the surrounding world; we explain that world with words, but words can never undo the fact that we are surrounded by it. The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled.”

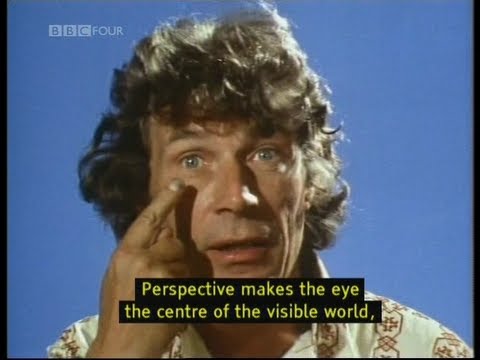

Published in 1972, it was based on a famous BBC television series, which was widely dubbed as an “eye-opener", demystifying the ways we were historically and socially conditioned to mystify text, silences, sounds, words, especially images, especially the female image.

Inspired by Walter Benjamin’s epical essay: The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, he was hailed as “liberator of images” by critics and a narrator who broke a new threshold in cultural studies in demystifying the language of the male gaze, as much as the manner in which images and paintings have been constructed or reproduced. However, the most endearing quality, especially in the book, was the manner in which it was designed, and the way it reached out to the reader.

|

| Berger’s work was not only an eye-opener, it was also a cultural and anthropological study which was eternally open-ended. |

There is a certain innocence in its pages. As if the reader has lost her/his innocence and it is so crucial that it must be resurrected before it is completely lost in the realm of prejudices and clichés, driven by a deadly cocktail, whereby, in a perverse twist, the medieval or post-renaissance painting can very well become integrated with the modern advertising principle of the consumer society.

In that sense, the incisive depth and cruel beauty of the storytelling of Ways of Seeing was marked like a narrative which became eclectic and childlike, as if turning the pages into a story book for children.

Indeed, it was at once a part of the folk and oral tradition where words once floated in inherited time and space to time-past, and, then, the image became the dominant narrative which weaves the beginning and the end in time-present and time-future.

Truly speaking, in that remarkable sense, Berger’s work was not only an eye-opener, it was also a cultural and anthropological study which was eternally open-ended.

An unfolding story within another incomplete story, eyes within eyes, canvas within canvas, cracked mirrors between inverted mirrors, female nudity becoming flesh and flesh becoming male voyeurism and public spectacle, art becoming a commodity and a revelation, painting turning into advertising, the gaze becoming diverse, perverse, a universe.

A feudal landscape painting. Land as ownership. Till the eyes can see. The male gaze, the landlord’s gaze, the patriarch’s gaze, stretching beyond into the endless horizon. He is standing, upright, fully erect, looking at his vast land which he owns, beyond the sunset and the blue sky of the countryside. She is lying, submissive, at his command, perhaps beautiful and domesticated, loyal and obedient, following his gaze dutifully, like a controlled bird in a cage. Indeed, the "commissioned" painting proves that not only is she merely a part of his land and landscape, an ornament of male, feudal property, she is herself a willing object of his gaze.

Contrast it with an ad of a car, a perfume, an undergarment or designer outfit, or an opulent holiday in modern times, she is yet again being reproduced as a "sexy" moment of voyeurism, an ornament and moment of lust, merely enhancing the fetish, glorifying the longing of the commodity the ad wants to sell.

John Berger would say that the male gaze, the consumer market and the affluent society not only objectifies the female identity into a sex object and commodity, she, herself, objectifies her own self-image. She is compelled to become a commodity and object in her own eyes. In more ways than one, it is like a slave reproducing his or her own slavery.

| The consumer market and the affluent society not only objectifies the female identity into a sex object and commodity, she, herself, objectifies her own self-image. |

Wrote Berger in the Ways of Seeing, commenting on a frontal nude of a young girl holding a mirror in her hand. “You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting ‘Vanity,’ thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for you own pleasure.”

He reproduced painting after painting from European high art and its underbelly, before and after the renaissance, where the female nude is eternally helpless, being displayed as a public spectacle, often as a "commissioned" portrait and painting by the spectator-owner.

She is often an object of collective male gaze, fully aware of her nudity as a spectacle, stunningly turned submissive, her naked body like a statue suspended in belief and disbelief, her eyes staring at the voyeur, who is also the painter, and, perhaps, the photographer, editor, copywriter and the cameraman. She is passive, he is dynamic, the conquerer, the usurper, the spectator-owner. His gaze owns her.

Wrote Berger, “One might simplify this by saying: men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object - and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.”

And not only the female image, anything and everything can be appropriated, all signs and symbols, like the Che Guevara image. An undergarment can be sold under the flag of "revolution". Freedom means an exotic wife, an opulent house, a swanky car. Love is a pain-killer. Fair and handsome is beautiful.

In the final analysis he enters the affluent society’s publicity and advertising industry, and breaks open the many layers of fetish and illusion, which marks the consumer society. It is the insatiability of desire, which sustains the market, the infinite manufacturing of this desire. One desire can only be replaced by another, though everything remains the same.

“Capitalism survives by forcing the majority, whom it exploits, to define their own interests as narrowly as possible,” wrote Berger. “This was once achieved by extensive deprivation. Today, in the developed countries, it is being achieved by imposing a false standard of what is and what is not desirable.”

John Berger’s conclusion is lucid and categorical: “Publicity exercises an enormous influence and political phenomenon of great importance. But its offer is as narrow as its references are wide. It recognizes nothing except the power to acquire. All other human faculties or needs are made subsidiary to this power. All hopes are gathered together, made homogeneous, simplified, so that they become the intense yet vague, magical yet repeatable promise offered in every purchase. No other kind of hope or satisfaction or pleasure can any longer be envisaged within the culture of capitalism.”

Also read: When 'The Naked and the Nude' met Durga

Watch: John Berger's Ways of Seeing, Episode 1 (BBC)