How refugees of Partition inspire the youth of India and Pakistan

Setting up a Partition Museum, dedicated to those who lost their homes (and sometimes their lives) in 1947, when India became independent, has been a dream for many among the post-Partition generation.

But those who grew up with stable families, in one place, and years of association and belonging, might find it difficult to understand the anguish of losing your home, forever. Or so I thought.

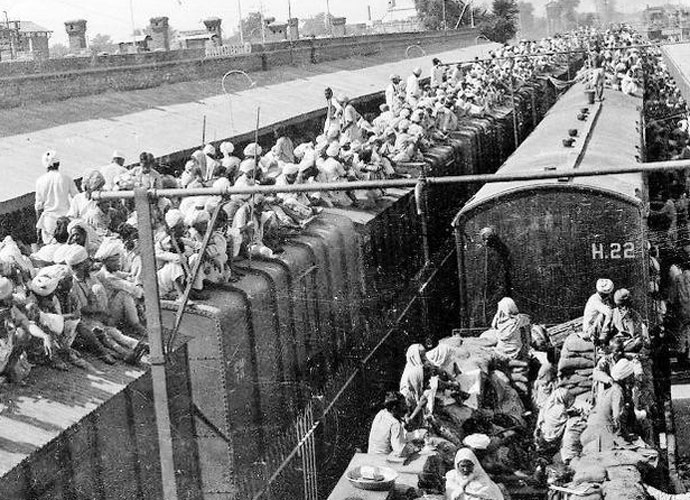

How could those who grew up in complete security ever know what it means to become a pariah, an unwanted person on the very streets where you once had friends? And then later, to undertake a long migration lasting weeks, sometimes months, to reach a refugee camp, with poor sanitation and no food or medication. To start life again, penniless, while the world was celebrating the birth of two nations, India and Pakistan. The irony of it all!

Yet, our recent experience, when we (at The Partition Museum Project) put up an exhibition called "Rising From The Dust: Hidden Tales From India's 1947 Refugee Camps" in Delhi, it showed us that there is a young generation growing up in India, that identifies with those who lost their identity, and their country.

After all, perhaps today, we all wonder who we are, a generous mix of myriad influences. And among those is a particular influence that might even have occurred prior to our birth, the Partition of India. Within that shared experience is far too much of baggage that we carry, concealed.

|

| Rich and poor had seen their lives reduced to dust and rubble, out of which they again lifted themselves. |

And is that surprising? There is so much talk about the rivalry between India and Pakistan that the young generation of today still gropes to understand our shared heritage. Imagine their surprise when they learn that they - on the other side - were one of us, till circumstances and politics forced the two asunder. Yet just a realisation could lead towards reconciliation, and lasting peace in the neighbourhood.

In our well attended exhibition, we mapped what Delhi might have looked like before the refugees arrived. And the large number of camps that suddenly sprung up all over. To recall that many of us are actually living upon the remains of those camps is interesting. In fact, as one speaker at our lecture series, Ratish Nanda, put it, it would be fascinating to go back to the remains of the camps in places like Purana Quila and actually dig through to discover where and how the refugees lived. All our recent history is buried in Delhi, around us.

Our exhibition had a steady, constant stream of visitors who arrived before the exhibition gallery officially opened and remained there till we had to request them politely to leave late in the evening.

Many visitors brought their parents or grandparents, who were partition survivors, to be recorded by our camera team. So many tears of nostalgia were shed during the eight days of our exhibition. There was enormous reiteration of the statement that we "must set up the Partition Museum soon". Fortunately, even though we are a small charity, that is our goal.

We found a lot of support from those who had no connect with the Partition, but were emotional over the pain they realised they had no inkling about. For learning more about what it must have been like in pre-Partition and post-Partition India, we had art, photographs, letters, objects, each one of which told a story, and that is what people came to see. To our pleasant surprise, even school children and teachers walked in, in large groups, to take copious notes.

What was indeed very touching were the tears that flowed freely as people walked through the narrative and understood some of the pain of those who made that difficult journey.

Rich and poor had seen their lives reduced to dust and rubble, out of which they again lifted themselves. Many of the stories of those refugees whom we had spoken about rebuilt their lives successfully, through hard work.

So as we move towards setting up the Partition Museum, later this year, we are borrowing from those refugees some of their determination, and grit.