What China’s Nepal inroads mean for India

Chinese planners have long dreamed of building a railway line connecting Tibet to Nepal and India, opening up what has historically been one of the world’s most isolated regions. The gravity-defying Qinghai-Tibet railway, a decade ago, opened up Tibet on its eastern frontiers, linking it for the first time with the Chinese hinterland. Planners have since dreamed of a similar opening up to the west, which would not only open Tibet’s economy but provide an avenue for China’s rapidly rising economic weight to spread beyond its borders.

Topography and financial viability have been two major hindrances. Adding to that has been New Delhi’s clearly evident unease at Beijing’s rising economic influence in a country that has long been dependent on India. Nepali officials, in the past, made clear that as long as New Delhi had worries about China, Kathmandu would never entertain the idea of opening up the country to a Chinese railway network.

The first two challenges remain, but it appears that the third has become much less of an issue for Nepal, possibly on account of the recent strains in its relations with New Delhi. For months, Kathmandu has been grappling with dire fuel shortages on account of the blockade along the border with India, which has followed protests in the bordering Madhesi region over the promulgation of the Constitution. Differences with India over the Constitution and the blockade have appeared to add urgency to Kathmandu’s efforts to diversify its dependence on India. In recent months, Nepal has courted China for fuel imports to tackle its energy crisis.

It was against this backdrop that Nepal Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli travelled to China. In Beijing on Monday, Oli signalled what could emerge as a transformative shift in how Kathmandu conducts relations with its two biggest neighbours. In a meeting with his Chinese counterpart Li Keqiang in Beijing, Oli said Kathmandu was on board for the cross-border railway project linking Tibet with Nepal, and would also seek Chinese assistance to build rail lines linking three of Nepal’s biggest cities – Kathmandu, Pokhara and Lumbini.

Chinese officials made it a point to note that the request for the railway line came from Nepal lest it be seen as a Chinese provocation aimed at India. But it is no secret that this has long been a goal of Chinese planners. While China responded "positively" to the proposal and agreed to begin a feasibility study "at an early date", sizeable challenges certainly remain, as Chinese officials acknowledged on Monday. They would move forward depending on the geography and technical and financial viability (although one wouldn’t bet on these posing too much of an obstacle, with Beijing only earlier this month announcing a second major railway project on the Tibetan plateau, following the Qinghai-Tibet rail, which would connect Chengdu in Sichuan province with Lhasa).

During his Beijing visit, Oli also secured a long-expected transit trade agreement with China, which would for the first time open up its ports to landlocked Nepal for trade. Some observers suggest this deal, too, was perhaps as much about the symbolism as it was about commerce. China’s eastern ports are three times the distance of Kolkata. But the agreement now signals that landlocked Nepal is longer dependent on India for transit access.

|

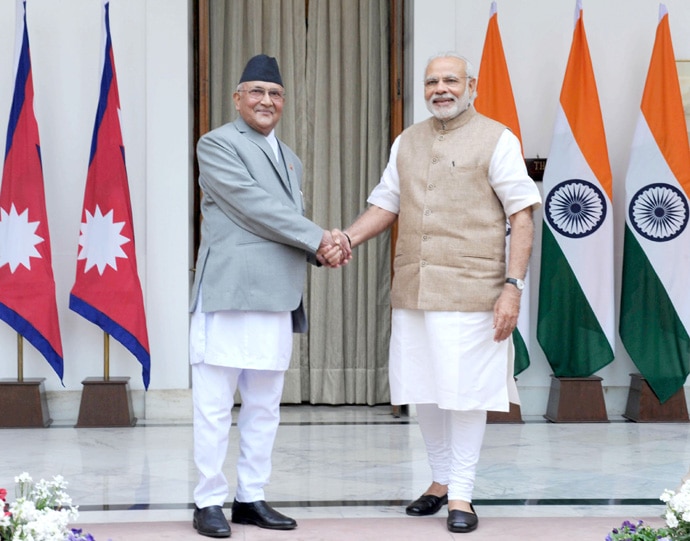

| Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi (right) with his Nepalese counterpart KP Sharma Oli in New Delhi on February 20, 2016. |

A Communist Party-run tabloid, the Global Times, used the occasion to tell India that it “should wake up to the fact that Nepal is a sovereign country, not a vassal of India’s”. The Chinese President, Xi Jinping, had a more diplomatic message for New Delhi, telling Oli that Nepal “can be a bridge between China and India”. Xi, in fact, suggested to Prime Minister Narendra Modi when they met in China last year that China envisioned an economic corridor linking the three countries, as part of his "Silk Road" pet initiative, including extending railway lines from Tibet, through Nepal, to India.

New Delhi now faces the dilemma of either staying away from what is emerging as an inevitability, or signing on to an initiative that will hasten China's regional economic dominance. For the time being, at least, Delhi is unlikely to come on board to Beijing's plans, wary as it has been of China's regional economic initiatives.

It was no surprise that Indian officials have downplayed the March 21 agreements, pointing out, rightly, that India’s ties with Nepal were of a far higher scale than China’s, with 98 per cent of Nepal’s external trade going through India.

That Nepal would seek closer economic ties with its neighbour to the east has perhaps always been on the cards. Every country seeks a balance in its external relations. And in China’s case, its rapid economic rise has pulled in almost every neighbour into its vast economic orbit. Yet the speed with which relations are being transformed will likely come as a surprise to New Delhi, which would have, a few years ago, discounted the likelihood of a Nepali leader travelling to Beijing, and asking for a cross-border railway to be built, as sheer fantasy.