A tribute to India's 'greatest scholar artist' KG Subramanyan

In January this year, I had the privilege of informing KG Subramanyan that he was being awarded the first-ever India Today Doyen of Indian Art Award for 2016.

"Well, it's about time," he snapped, not unkindly.

But he was in much too ill-health to travel for the ceremony, though his wit remained sharp, his language erudite, and his gently chastising temper always edged with good humour.

"If you wanted me to travel, you should have thought of this earlier, shouldn't you?" he admonished, laughing.

His diminutive daughter Uma Padmanabhan travelled on his behalf.

What he did want, however, was a small ceremony in Vadodara, where he had taught and mentored generations of our greatest artists at the Faculty of Fine Arts at the MS University, since 1951.

His students were everything to him and, it was as though, while the stalwarts of the Baroda school spread their wings and left, it was Subramanyam who held down the roost.

He did not seek acknowledgement from those who had passed out through his hands as much as he gained his sustenance from them and from nourishing them in turn. It was not his only alma mater that he would return to.

|

| KG Subramanyan has been touted 'India's greatest scholar artist'. |

Fondly referred to as "Manida", the name originated in his formative years as an artist at Santiniketan, in 1944. He returned to teach there for nine years in 1980. And that was the second reason why Manida would not travel to Delhi.

As he turned 92 on February 5, 2016, he was reserving all his strength to travel back to the crucible of his art, to create an archive and an endowment of his home in the name of Benode Behari, one of the greatest muralists India ever saw, and to whom Subramanyan served as apprentice during his Hindi Bhawan murals with their egalitarian bhakti bhawa phase.

He drew the importance of structure and drawing from Nandalal Bose and in these strands he absorbed Santiniketan into his being. Yet he broke away from them enough to grow beyond them. Drawing from nature, he yet rarely drew nature, focusing on the deconstructed gesture of the human form. This philosophy of coexistence of separate intellectual strands was to be an influence that would forever etch murals into his oeuvre.

His Sketches, Scribbles and Drawings, an exhibit that opened in Santiniketan on his birthday, held glimpses of his writings from across the ages, reminisces about everyone from a "Ms Know It All" to Nandalal Bose and Rabindranath Tagore and Hemen Majumdar written with his typical breezy, but biting humour.

The loss of Manida, on this rainy afternoon in June, 2016 in Baroda is what senior artist Atul Dodiya laments as the loss of "India's greatest scholar artist".

|

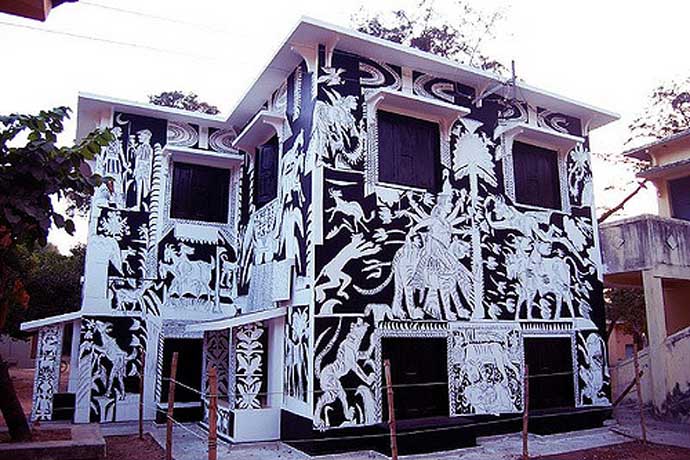

| Subramanyan's murals have fused Indian tradition of folklore, myth and contemporary art. |

Though he self-deprecatingly referred to himself as "muddle headed", he was an economist trained at Presidency College, Madras. He was imprisoned during the Independence struggle, working closely with Mahatma Gandhi, and wearing only khadi till the day he died.

Geetha Mehra gallerist at Sakshi Art Gallery, who met him just two weeks ago as he underwent a second hip surgery from which everyone expected him to make a full recovery, calls him, "the last of that era of Gandhians, ram-rod straight and speaking what he meant".

Manida studied at the Slade School of Art and was a Rockefeller Fellow in 1966. Manida wrote not only essays and ruminations but books on art as well as for children, writing out the stories and illustrating them himself in works such as When God First Made the Animals and The Tale of the Talking Face. The Living Tradition is his exposition on the need to draw from culture, while yet standing apart from it.

If he drew from Indian mythology, he associated it with life, and in such expanded the storytelling quality of his work.

Art to him was not a static force isolated from the rest of the thought world, it was that interconnectedness that flowed from it all, and was pushed by a creative force into something larger. His love of this pure knowledge laced his narratives with anecdotes, jumping from stories about artists to politicians and literature and world history, to make his point.Manida's passing came as a shock to many, as he was a fighter, sprightly, and everyone presumed he would pull through his illnesses, Mrs Kiran Nadar tells me on the phone from London.

|

| KG Subramanyan's influences ranged from Tagore and Hokusai to Chinese practicality and poetry. |

Her collection includes Manida's "Construct Constructions", sketches and terracotta works, and her Kiran Nadar Museum of Arts plans to host a retrospective of the artist shortly.

"Freedom of expression was not something he merely stood for. He was it himself, in the range and intellectual prowess of his thought processes and in the texture, form and material he worked with. He able to be free and frank and generous," Nadar says.

His influences ranged from Tagore and Hokusai to Chinese practicality and poetry, apart from their ink and brush work on rice paper. He played - there is no other word for how Manida inserted his personality into art - with weaving, toy-making, fabric, glass and gouache, doodles, calligraphy and forms of painting itself using ink, ballpoint, crayon, pen and brush and more recently, enamel.

In a lecture that Manida delivered shortly before his birthday at Darshak Itihas Nidhi, a not-for-profit research organisation for history in Gujarat - and not one to shy away from the moot point - Manida managed a commentary on PM Narendra Modi's Smart Cities, the Make In India campaign, Nobel Peace Prize winner Mohammad Younus, Twitter and Facebook turning the world into a tower of Babel, and pushed, instead of focusing on art, or himself, his contributions, his students, or his endowment, for "smart villages" and equal growth.

|

| Subramanyan's War of the Relics, one of his last murals, has epic ambition and scale. |

His War of the Relics (2012), which was commissioned by Mehra so the world would be able to see a mural of his outside of Santiniketan, and now one of his seminal works, was undertaken by him when he was almot touching 90. It is a complex combination of mythical war and modern violence, a comment on the history of our age of conflict.

Manida was never an artist past his prime, he was always an artist in the moment, in the day, in the age, till the day he died.

|

| Subramanyan was greatly taken with experiments of texture and material and form. |

He was greatly taken with experiments of texture and material and form. His first forays into Slade had him struggle to make the leap from cultural loudness that his Kerala roots brought to what he referred to as "cultivated blandness". Here he discovered his schema, a schematic infrastructure which shaped their particular way of seeing, which he began to search for amongst the museums of Europe.

Unlike contemporaries who were busy rejecting the past, Manida said: "In truth, museums are where you see yourself better in the middle of the rest."

Loved by students across the spectrum, from Baroda to Bangladesh, he was a gentle giant and a colossus of a mentor.

Before Dodiya had even had his first solo show, in the late 1980s, Manida, even then a colossus, took a rickshaw to visit his studio and give him observations on his work. "You cannot imagine the impact of that on an artist who hasn't even started out," says Dodiya, who a few years ago, offered himself up as Manida's assistant to paint all of Santiniketan with his murals after watching him repaint an entire mural at the age of 89.

Naveen Kishore, friend and patron of the Seagull Foundation, says Manida lived a full life, in the partaking and sharing of knowledge, humour, understanding and perspective he and all he drew in, came full circle.

"He would not have wanted his friends to be devastated," Kishore says. The last lines of Manida's essay on himself, pertaining to an old Chinese poem he had fondly kept, read:

"Someone mourns the death of a singing girl he was attached to. Without howling or beating his breast. Inscribing his grief on the things around.

- Dew on the secret orchid

- Like screaming eyes.

- Nowhere the hearts bound as one.

- Evanescent flowers I cannot bear to cut.

- Grass like a cushion.

- The pine like a parasol.

- The wind is a skirt,

- The waters are tinkling pendants.

- A coach with lacquered sides

- Waits for someone in the evening.

- The cold green will-o-the-wisp

- Squanders its brightness

- Beneath West Mound

- The wind puffs rain."